Films in Flashback.

While many directors and screenplay writers employ the flashback as a tool to enhance a character’s background or provide additional information to a scene, there are those films that are narrated almost in their entirety in flashback. A central character, a protagonist, narrates the unfolding story to another character onscreen and therefore in turn to the audience either as the story unfolds in the book or as their memory of events.

- The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Wes Anderson

- The Notebook (2004) Nick Cassavetes

- The Limey (1999) Steven Soderbergh

These films have very little in common other than that they are narrated entirely in flashback. In The Notebook (2004) the character Duke, played by James Garner reads from his notebook to a another resident Mrs Hamilton in a nursing home played by Gena Rowlands about the life of a young couple who met and fell in love in the 1940’s and before America entered the war in Europe. The premise of the film until the very end is that Garners character is reading the story of this young couple, Noah and Allie, in the 3rd person, as Allie’s character played by Rowlands is in late stage Dementia and remembers very little if anything of her past life, including family or friends and doesn’t even remember that Duke played by Garner has read this story to her many times. Later in the film we learn that is Duke is actually Noah and is telling their story as Mrs Hamilton, Rowlands (Allie) is his wife and they are the young couple featured in the story (Cassavetes, 2004)

These films have very little in common other than that they are narrated entirely in flashback. In The Notebook (2004) the character Duke, played by James Garner reads from his notebook to a another resident Mrs Hamilton in a nursing home played by Gena Rowlands about the life of a young couple who met and fell in love in the 1940’s and before America entered the war in Europe. The premise of the film until the very end is that Garners character is reading the story of this young couple, Noah and Allie, in the 3rd person, as Allie’s character played by Rowlands is in late stage Dementia and remembers very little if anything of her past life, including family or friends and doesn’t even remember that Duke played by Garner has read this story to her many times. Later in the film we learn that is Duke is actually Noah and is telling their story as Mrs Hamilton, Rowlands (Allie) is his wife and they are the young couple featured in the story (Cassavetes, 2004)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Interestingly, the story is told entirely in flashback by the Author (the young writer, played by Jude Law) who is actually retelling the story of another main character in the film Mr Mustafa (Zero), it is Mustafa’s memories of the events involving himself and his association with the other main character, Monsieur Gustave H (played by Ralph Fiennes) and the series of misadventures, that befall them when trying to claim the contents of a will, the valuable painting of ‘Boy with apple’. (Anderson, 2014)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Interestingly, the story is told entirely in flashback by the Author (the young writer, played by Jude Law) who is actually retelling the story of another main character in the film Mr Mustafa (Zero), it is Mustafa’s memories of the events involving himself and his association with the other main character, Monsieur Gustave H (played by Ralph Fiennes) and the series of misadventures, that befall them when trying to claim the contents of a will, the valuable painting of ‘Boy with apple’. (Anderson, 2014)

In both these films there is no obvious cinematic device used to differentiate between the current timeline and the past timeline, by this I mean a dissolve or blurring of the image but the jump in timeline is differentiated by a change in look and character. in The Notebook (2004) it is the opening of the notebook and as Duke (Garner) begins to read, the timeline switches to the 1940’s and the audience can identify with the change, this transition as the characters also change to their younger selves, they are played by the younger actors, Duke (Noah) played by Ryan Gosling and Mrs Hamilton (Allie) played by Rachel McAdams. However, in The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) while there are no obvious uses of the flashback visual tools, that is a cut to a dissolve or blurring to identify the shift from the timeline of the Authors meeting with Mr Mustafa that is, Zero (set in the 1960s) and the recounted timeline (1930’s) however there is a marked change in the production design (Colours) and the choice of cinematic aspect ratio with the 1980’s shot in 1:85.1 format, the 1960’s in 2:35.1 widescreen anamorphic and finally the 1930’s shot in academy ratio 1:375.1. The hotel in the 1960’s is drab, mainly brown or as Wes says “his idea of the communist era, which is olive green and orange” while also appearing run down, meanwhile the 1930’s Hotel is bright, very pink and vibrant like a “wedding cake”. (Wes Anderson on the Colors and Ratios of ’The Grand Budapest Hotel – YouTube, 2015)

The Limey (1999) Interesting example of the use of flashbacks, with the creative use of the editing process that seems to make it appear as if the film is always looking backwards or as the Director suggests, representing the fragmentation of Wilsons memory. There are flashbacks within flashbacks and flashbacks looking much further back, into a past with a young Wilson and young Jenny, these flashbacks were dropped into the edit from another film directed by Ken Loach, Poor Cow (1967) this works so well that the audience doesn’t have to imagine a younger Wilson or Jenny they can link directly through to the characters past and Wilsons memories of a young Jenny in the use of footage showing a young Terence Stamp playing the role of a petty criminal in Poor Cow (1967).

The Limey (1999) Interesting example of the use of flashbacks, with the creative use of the editing process that seems to make it appear as if the film is always looking backwards or as the Director suggests, representing the fragmentation of Wilsons memory. There are flashbacks within flashbacks and flashbacks looking much further back, into a past with a young Wilson and young Jenny, these flashbacks were dropped into the edit from another film directed by Ken Loach, Poor Cow (1967) this works so well that the audience doesn’t have to imagine a younger Wilson or Jenny they can link directly through to the characters past and Wilsons memories of a young Jenny in the use of footage showing a young Terence Stamp playing the role of a petty criminal in Poor Cow (1967).

Of course, this somewhat relies on the audience not being aware that this footage is from another film made in 1967, however their use as a flashback make perfect sense. The grainy visuals from an earlier time using old film stock perfectly fitting into the flashback concept of showing memories from an earlier time. The film is designed, according to Soderbergh, to reflect on how human memory functions, we remember past events in fragments triggered by events, objects or any of the sensory inputs. “It’s a graphic depiction of the fragmentary nature of memory, editor Sarah Flack turning the shards of story into fleeting reflections that capture Jenny between shifting planes of recollection”. (Gurd, 2019) The same can be said of Wilson, his memories are fragmented, recollections of Jenny on the beach, her threatening to call the Police on him if he does anything bad, which later becomes important in the final scenes of the film and may have influenced Wilsons decision not to go through with the killing of Valentine. “Soderbergh creates an historical symmetry between past/present and Valentine/Wilson with identical scenes of Jenny as a young girl threatening to expose her father’s criminal activity and the older Jenny in a similar situation with Valentine (holding a telephone in both cases). The closer Wilson gets to the truth the more he comes to realize his own complicity as an absent father in her daughter’s death.” (Totaro, 2002)

Soderbergh says “Given its premise, it seemed there was some possibility to recraft it into a memory piece”. (Fear, 2019) Eduardo shares his experiences of being with Jenny through flashbacks, those of her confrontation with the men at the warehouse for example, the same men that Wilson later shoots dead after his beating at the warehouse.

Flashbacks triggered by a sound, a smell or indeed anything can trigger these memories and while in the film these triggers are not always visible on screen, we can imagine that they are there, experienced by Wilson, triggering these memories of his fragmented past life with his daughter, Jenny, while in and out of prison.

Wilson also experiences a flashforward, a prolepsis, initiated I suspect by Wilson finding a solitary photograph of his daughter, Jenny, at the top of the stairs, during his wandering around Valentines home, these flashforwards appear as alternative futures and all violent, in the scene when Wilson visualises the alternative options/outcomes of killing Valentine, by shooting him, only to be stopped at the moment of execution by Eduardo.

Wilson also experiences a flashforward, a prolepsis, initiated I suspect by Wilson finding a solitary photograph of his daughter, Jenny, at the top of the stairs, during his wandering around Valentines home, these flashforwards appear as alternative futures and all violent, in the scene when Wilson visualises the alternative options/outcomes of killing Valentine, by shooting him, only to be stopped at the moment of execution by Eduardo.

Soderbergh says “We created or tried to create, meaning and emotion through repetition and juxtaposition, which again, is something that’s unique to movies. The ability to mold something and then change the meaning or alter the meaning just by reordering and repeating things, that’s unique in film.” (Boucher, 2019)

What is the purpose of the Flashback?

In The Notebook (2004) the flashbacks are like many examples of the flashback usage in film, it is used to link to a past, a past in this case forgotten in its entirety by Allie. Duke uses the notebook as a form of misdirection, so as not to be seen as recalling from his own memories, in the retelling of what is their story. Duke appears to read from his book in the hope that Allie will regain her memory of their past life together through his readings. In many respects this misdirection works, as Allie believes the story is of a couple unknown to her, just an interesting story of young love until she has a lucid moment and she remembers that Duke is her husband and the story he has been telling her, is their own. One of the possible reasons for this filmmaking approach is to also keep the audience guessing until the point in the film that it becomes clear that they and the young couple visited in the flashbacks are one and the same and then from this point to keep the audience interest and the suspense, in the hope that at some point Allie will remember their past life together.

In The Notebook (2004) the flashbacks are like many examples of the flashback usage in film, it is used to link to a past, a past in this case forgotten in its entirety by Allie. Duke uses the notebook as a form of misdirection, so as not to be seen as recalling from his own memories, in the retelling of what is their story. Duke appears to read from his book in the hope that Allie will regain her memory of their past life together through his readings. In many respects this misdirection works, as Allie believes the story is of a couple unknown to her, just an interesting story of young love until she has a lucid moment and she remembers that Duke is her husband and the story he has been telling her, is their own. One of the possible reasons for this filmmaking approach is to also keep the audience guessing until the point in the film that it becomes clear that they and the young couple visited in the flashbacks are one and the same and then from this point to keep the audience interest and the suspense, in the hope that at some point Allie will remember their past life together.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) from the opening scene, of the girl at the statue of the Author, she is carrying a copy of his book and we assume that from this book the whole film is told in a flashback through each of its different times of the past life of the author and the past life through the memories of Mustafa retold from his initial meeting with Mustafa in the spa and then continued at a shared evening meal in the hotels restaurant. In many respects a similar approach to that used in The Notebook (2004). Anderson himself relates that the idea for the film came from a series of books that he was reading by Austrian author Stefan Zweig. “The Grand Budapest Hotel has elements that were sort of stolen from both these books. Two characters in our story are vaguely meant to represent Zweig himself — our “Author” character, played by Tom Wilkinson” (Prochnik, 2014)

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) from the opening scene, of the girl at the statue of the Author, she is carrying a copy of his book and we assume that from this book the whole film is told in a flashback through each of its different times of the past life of the author and the past life through the memories of Mustafa retold from his initial meeting with Mustafa in the spa and then continued at a shared evening meal in the hotels restaurant. In many respects a similar approach to that used in The Notebook (2004). Anderson himself relates that the idea for the film came from a series of books that he was reading by Austrian author Stefan Zweig. “The Grand Budapest Hotel has elements that were sort of stolen from both these books. Two characters in our story are vaguely meant to represent Zweig himself — our “Author” character, played by Tom Wilkinson” (Prochnik, 2014)

Note: It would be interesting to consider films that also use this approach, that is, the concept of reading from a book to tell a story in flashback, for example The Never Ending Story (1984) and The Princess Bride (1987)

The Limey (1999) This film was effectively created in the post-production stage, in the editing processes. We learn from interviews with the director Steven Soderbergh that the first edit of the film was in a typical linear progression and then following a screening he decided with his editor to fragment the footage by creating a non-linear timeline using flashbacks for the film, to better represent the seemingly fragmented memory and to explain the actions of Wilson. We return to the same shot of Wilson seated on the plane several times, these seemingly breaking up the linear sequence or returning the audience through flashbacks to the current timeline and with this also to Wilsons thought processes. So, I feel it is this single shot of Wilson seated on the plane returning to London, which initiates the flashbacks and what can be the confusion of a film that is always looking backwards.

Confusingly one of these images of Wilson on the plane can also be seen as a flashforward, the first time we see Wilson seated on the plane at the beginning of the film, which seems to be of him travelling from London to the America but is actually the direct opposite. The opening sequence of Wilson shot at the Los Angeles airport, is of his departure back to London, we never see his London departure or his arrival in Los Angeles. The subsequent on plane images seemingly preceding flashbacks to his pursuit of revenge for his daughters killing. Totaro thinks that “To read that first airplane image as a flashforward and the film a flashback makes sense of most of the film, but not all because there are several scenes in which Wilson could not have been present.” (Totaro, 2002) I’m not sure if I am in total agreement with this statement because like all memories they can be derived from actual experience or based on inference and imagination of a situation or event, indeed a collective memory.

The flashback is a privileged moment in unfolding that juxtaposes different moments of temporal reference. A juncture is wrought between present and past and two concepts are implied in this juncture: memory and history. (Turim, 2013)

Memory loss, erasure and representation in flashback

Bibliography

Anderson, W. (2014) The Grand Budapest Hotel · BoB. Available at: https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/07CA758B?bcast=130244766 (Accessed: 31 January 2020).

Boucher, G. (2019) ‘The Limey’ At 20: Steven Soderbergh Revisits His “Vortex Of Terror” – Deadline. Available at: https://deadline.com/2019/12/steven-soderbergh-looks-back-the-limey-his-personal-vortex-of-terror-1202792732/ (Accessed: 10 February 2020).

Cassavetes, N. (2004) The Notebook. Amazon Prime. Available at: ONLINE Accessed 30/01/2020.

Fear, D. (2019) Steven Soderbergh on the 20th Anniversary of ‘The Limey’ – Rolling Stone. Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-features/steven-soderbergh-interview-20th-anniversary-limey-921006/ (Accessed: 5 February 2020).

Gurd, J. (2019) Reflections Of Jenny: THE LIMEY At 20 | Birth.Movies.Death. Available at: https://birthmoviesdeath.com/2019/10/07/reflections-of-jenny-the-limey-at-20 (Accessed: 4 February 2020).

Prochnik, G. (2014) ‘I stole from Stefan Zweig’: Wes Anderson on the author who inspired his latest movie – Telegraph. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/10684250/I-stole-from-Stefan-Zweig-Wes-Anderson-on-the-author-who-inspired-his-latest-movie.html (Accessed: 10 February 2020).

Totaro, D. (2002) The Limey – Offscreen. Available at: https://offscreen.com/view/limey (Accessed: 10 February 2020).

Turim, M. (2013) Flashbacks in film: Memory & history, Flashbacks in Film: Memory & History. Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9781315851761.

Wes Anderson on the Colors and Ratios of ’The Grand Budapest Hotell – YouTube (2015). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ouavfP6EhWQ (Accessed: 3 February 2020).

Journal entry are examples of my PhD research and research progress. They may include essays, extensive notes and even videos. A Journal entry isn’t usually a predictable addition as I will upload these on completion of a small project or essay so they tend to be uploaded at random times and dates. What should you keep in a research journal? I immediately thought it should be notes you’ve made on articles and journal documents that you have read. Adding a few references to look up at a later time or to include in your thesis. I made a decision to only use my journal for projects and specific research around my film practice. I created a separate category on this blog for my notes and references. The idea behind this was to just make it easier to find data. If it’s a note I look in notes anything else it’s probably in my journal. Also Journals tend to be longer entries with research, conclusions and reflection but a note is just that a note to myself and maybe others re. my research.

Journal entry are examples of my PhD research and research progress. They may include essays, extensive notes and even videos. A Journal entry isn’t usually a predictable addition as I will upload these on completion of a small project or essay so they tend to be uploaded at random times and dates. What should you keep in a research journal? I immediately thought it should be notes you’ve made on articles and journal documents that you have read. Adding a few references to look up at a later time or to include in your thesis. I made a decision to only use my journal for projects and specific research around my film practice. I created a separate category on this blog for my notes and references. The idea behind this was to just make it easier to find data. If it’s a note I look in notes anything else it’s probably in my journal. Also Journals tend to be longer entries with research, conclusions and reflection but a note is just that a note to myself and maybe others re. my research.

Alita is a confusing film, the narrative is familiar and initially the audience may be thinking, is this a film for children? In what appears to be another representation of a dystopian future, a broken world recovering from war, this time an interplanetary war with Mars, The Fall, the broken remains of the cyborg battle angel, Alita is salvaged from the detritus discarded and piled high below a futuristic city called Zalem hovering above the ruins of the Iron city. A film for children it is not, or at least 12+ and followers of Anime, but it is also a film for adults, it has some of the elements of the Transformers films, themselves based on children’s toys and television programs of the same name. The character designs are familiar, a melange of many styles from films of the Science Fiction genre. The narrative shares some elements of several films not only from the science fiction genre, for example there are many similarities with the Bourne Trilogy, by this I mean an agent, in this case Alita, a cyborg with no memory of her past or previous identity, as in Bourne Identity (2002), Bourne also designed to be a weapon an asset, albeit in Alita’s case from a distant past, with a long forgotten mission. The loss of memory in itself also creates a loss of identity, Alita does not know who she is and what her purpose in life is. This becomes a key element in the development of the narrative as Alita embarks on a new mission and seeks to recover her memories and therefore a new identity. There are visual references to the film Avatar in the production design, you can see and feel David Cameron’s hand in this production, the oversize eyes of Alita sharing a similarity to the ‘Na Vi’ in Avatar. But this is a story as much as anything about memory loss and initially it appears after reconstruction that Alita’s memory loss is complete until we see in a memory flashback, memories of a military past (combat on the moon scene), the memory appeared to be triggered by violent action, when attacked and there is risk to life, Alita instinctively assumes a fighting stance and defeats her father’s attackers, that is Dr Dyson Ido.

Alita is a confusing film, the narrative is familiar and initially the audience may be thinking, is this a film for children? In what appears to be another representation of a dystopian future, a broken world recovering from war, this time an interplanetary war with Mars, The Fall, the broken remains of the cyborg battle angel, Alita is salvaged from the detritus discarded and piled high below a futuristic city called Zalem hovering above the ruins of the Iron city. A film for children it is not, or at least 12+ and followers of Anime, but it is also a film for adults, it has some of the elements of the Transformers films, themselves based on children’s toys and television programs of the same name. The character designs are familiar, a melange of many styles from films of the Science Fiction genre. The narrative shares some elements of several films not only from the science fiction genre, for example there are many similarities with the Bourne Trilogy, by this I mean an agent, in this case Alita, a cyborg with no memory of her past or previous identity, as in Bourne Identity (2002), Bourne also designed to be a weapon an asset, albeit in Alita’s case from a distant past, with a long forgotten mission. The loss of memory in itself also creates a loss of identity, Alita does not know who she is and what her purpose in life is. This becomes a key element in the development of the narrative as Alita embarks on a new mission and seeks to recover her memories and therefore a new identity. There are visual references to the film Avatar in the production design, you can see and feel David Cameron’s hand in this production, the oversize eyes of Alita sharing a similarity to the ‘Na Vi’ in Avatar. But this is a story as much as anything about memory loss and initially it appears after reconstruction that Alita’s memory loss is complete until we see in a memory flashback, memories of a military past (combat on the moon scene), the memory appeared to be triggered by violent action, when attacked and there is risk to life, Alita instinctively assumes a fighting stance and defeats her father’s attackers, that is Dr Dyson Ido. Alita is determined to learn more of her past and forms a plan of action to enter the ultra-violent cyborg games, Motorball, which appears to be a virtual copy of Rollerball (1975) but for cyborgs. Actually, the film appears to borrow ideas and narratives from several other films, for example, the street scenes in the Iron city reminds me of the films Fifth Element (1997) and the more recent film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017) both by the director Luc Besson. Perhaps David Cameron is a fan of Luc Besson’s films? The film Alita: Battle Angel (2019) had mixed reviews but is the first film to come out of Lightstorm Entertainment, the studio set up by David Cameron and the first film to capitalise on the visual technology and expertise of the special effects created for the production of Avatar (2014) and while there can be no doubting the excellence of these visual effects, the narrative is relatively weak, seemingly borrowed from several films. This is not a new issue as that was also identified in the Avatar (2009) narrative, directed by James Cameron, which performed exceptionally well at the box office but failed to impress critics due in part to the screenplay, which many considered a rewrite of the story of Pocahontas, personally I felt this was an oversimplification, as in any narrative that has at its core the idea of an advanced civilisation making contact with a less advanced civilisation would come into this category.

Alita is determined to learn more of her past and forms a plan of action to enter the ultra-violent cyborg games, Motorball, which appears to be a virtual copy of Rollerball (1975) but for cyborgs. Actually, the film appears to borrow ideas and narratives from several other films, for example, the street scenes in the Iron city reminds me of the films Fifth Element (1997) and the more recent film Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017) both by the director Luc Besson. Perhaps David Cameron is a fan of Luc Besson’s films? The film Alita: Battle Angel (2019) had mixed reviews but is the first film to come out of Lightstorm Entertainment, the studio set up by David Cameron and the first film to capitalise on the visual technology and expertise of the special effects created for the production of Avatar (2014) and while there can be no doubting the excellence of these visual effects, the narrative is relatively weak, seemingly borrowed from several films. This is not a new issue as that was also identified in the Avatar (2009) narrative, directed by James Cameron, which performed exceptionally well at the box office but failed to impress critics due in part to the screenplay, which many considered a rewrite of the story of Pocahontas, personally I felt this was an oversimplification, as in any narrative that has at its core the idea of an advanced civilisation making contact with a less advanced civilisation would come into this category. Ghost in the Shell (2017) This film, a live action version of the anime film also called Ghost in the Shell (1995) shares much with Alita: Battle Angel (2019) for example the main protagonist, Major Mira Killian is also a cyborg with no memory of her previous life, she only has memories from the time that she was first awakened as a cyborg, her life as a human is blank with the exception of the false memories created by the Hanka scientists who inserted a cover memory for a past she never had, the memory of losing her parents in a terrorist attack and leaving her body badly injured and only her brain surviving the attack. The brain living on in a mechanical body, which is called a shell, hence the title of the film Ghost in the Shell. Major experiences random memories as flashbacks In what appears, and are described by the Hanka scientists as glitches in her program, Major sees images of locations and objects flash into and out of existence, but rather than glitches in her program these are true memories from her past that are leaking through the chemically induced memory blocks created by the Hanka scientists, these are real memory flashbacks to her life before becoming a cyborg.

Ghost in the Shell (2017) This film, a live action version of the anime film also called Ghost in the Shell (1995) shares much with Alita: Battle Angel (2019) for example the main protagonist, Major Mira Killian is also a cyborg with no memory of her previous life, she only has memories from the time that she was first awakened as a cyborg, her life as a human is blank with the exception of the false memories created by the Hanka scientists who inserted a cover memory for a past she never had, the memory of losing her parents in a terrorist attack and leaving her body badly injured and only her brain surviving the attack. The brain living on in a mechanical body, which is called a shell, hence the title of the film Ghost in the Shell. Major experiences random memories as flashbacks In what appears, and are described by the Hanka scientists as glitches in her program, Major sees images of locations and objects flash into and out of existence, but rather than glitches in her program these are true memories from her past that are leaking through the chemically induced memory blocks created by the Hanka scientists, these are real memory flashbacks to her life before becoming a cyborg.  The flashbacks appear randomly throughout the film, unlike other films using flashbacks there appears to be no obvious triggers, the only clue being the visuals, the glitching images, pixilation and colours to indicate these are flashback memories. Killian (Major) is captured by Kuze who connects her to his network but then releases her, at this point she sees the image of the shrine the one from her flashbacks on his chest linking Kuze to Killian. Kuze reveals he was also a product of the project 2571, a failure, one of 98 and now seeking revenge for what they did to him. Killian returns to confront Dr Oulet who is under orders from Cutter to terminate Killian, but instead Dr Oulet disobeys and instead gives Killian an address to go to and rekindle her lost memories. Dr Oulet pays for this disloyalty and is killed by Cutter.

The flashbacks appear randomly throughout the film, unlike other films using flashbacks there appears to be no obvious triggers, the only clue being the visuals, the glitching images, pixilation and colours to indicate these are flashback memories. Killian (Major) is captured by Kuze who connects her to his network but then releases her, at this point she sees the image of the shrine the one from her flashbacks on his chest linking Kuze to Killian. Kuze reveals he was also a product of the project 2571, a failure, one of 98 and now seeking revenge for what they did to him. Killian returns to confront Dr Oulet who is under orders from Cutter to terminate Killian, but instead Dr Oulet disobeys and instead gives Killian an address to go to and rekindle her lost memories. Dr Oulet pays for this disloyalty and is killed by Cutter.  Killian steals a motorcycle and goes to the address where she finds the shrine that appears in all her flashbacks, she flashes back to the start of it all, images of Cutter and his men attacking and dragging away the children, runaways for use in their experiment’s to create the perfect cyborg. This is Killian’s beginning, not a survivor of a cyber terrorist attack but abducted by Cutter for his experiments at Hanka. Kuze joins her at the shrine and he reveals her real name as Motoko Kusanagi, that they were friends and abducted together. (Opam, 2017)

Killian steals a motorcycle and goes to the address where she finds the shrine that appears in all her flashbacks, she flashes back to the start of it all, images of Cutter and his men attacking and dragging away the children, runaways for use in their experiment’s to create the perfect cyborg. This is Killian’s beginning, not a survivor of a cyber terrorist attack but abducted by Cutter for his experiments at Hanka. Kuze joins her at the shrine and he reveals her real name as Motoko Kusanagi, that they were friends and abducted together. (Opam, 2017) Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2014) this can be a confusing film in many ways but it the case of flashbacks the audience does not always get an obvious indication or what the trigger is or of where they are in the films timeline, whether they are watching in real time or a memory in a Flashback sequence and in many cases the only way of identifying whether this is a memory or real time is by working out where this sequence fits into the he narrative of the film. However, the scenes where Joel (played by Jim Carrey) appears seemingly to be in real time on valentine’s day in the bookshop where Joel confronts Clementine (played by Kate Winslet) is confusing is this real time or a flashback? Clementine in this scene appears to have no memory of their relationship and also appears to be involved in a new relationship with a character hidden from sight (who we later learn is Patrick played by Elijah Wood). However the Director then uses the lighting in the bookshop to represent and indicate this scene is actually a flashback by turning the lights off in sequence and as they follow Joel as he appears to leave the bookshop but actually appears to go directly into another memory this time he is talking to his friends in their home, and this is where he learns Clementine has had her memory erased of him by seeing the card from Lacuna.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2014) this can be a confusing film in many ways but it the case of flashbacks the audience does not always get an obvious indication or what the trigger is or of where they are in the films timeline, whether they are watching in real time or a memory in a Flashback sequence and in many cases the only way of identifying whether this is a memory or real time is by working out where this sequence fits into the he narrative of the film. However, the scenes where Joel (played by Jim Carrey) appears seemingly to be in real time on valentine’s day in the bookshop where Joel confronts Clementine (played by Kate Winslet) is confusing is this real time or a flashback? Clementine in this scene appears to have no memory of their relationship and also appears to be involved in a new relationship with a character hidden from sight (who we later learn is Patrick played by Elijah Wood). However the Director then uses the lighting in the bookshop to represent and indicate this scene is actually a flashback by turning the lights off in sequence and as they follow Joel as he appears to leave the bookshop but actually appears to go directly into another memory this time he is talking to his friends in their home, and this is where he learns Clementine has had her memory erased of him by seeing the card from Lacuna.  I concur, the sequence of Joel in the bookshop was also a flashback but there was no indication beforehand, but this explanation seems to fit into the timeline. It is at this point where Joel learns of Clementine’s decision to erase him from her memory and so Joel decides to do the same.

I concur, the sequence of Joel in the bookshop was also a flashback but there was no indication beforehand, but this explanation seems to fit into the timeline. It is at this point where Joel learns of Clementine’s decision to erase him from her memory and so Joel decides to do the same. Well I’m not sure how they both subconsciously knew to meet there, as we are only witnesses to Joel’s memory erasure, so how did Clementine know, or have reason to go to Montauk that day? Mary the clinics secretary, who we learn later has also had her memory erased because of a previous relationship with Howard, quotes Friedrich Nietzsch “Blessed are the forgetful for they got the better even of their blunder” and again this time Alexander Pope “How happy is the blameless vessels lot! The world forgot. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” The first quote appears to indicate that the erasure of their memories solves all their problems but of course it does not do that at all, in fact they both appear to have major identity issues, having lost part of themselves by having the memories of each other erased. Each looking for what they have lost, Clementine almost at the edge of madness as she searches her home for what? In the article by Gemma King “I don’t know. I’m lost. I’m scared. I feel like I’m disappearing . . . nothing makes sense to me.” It is clear that Clementine feels the rupture in the continuity of her experience caused by the erasure, verbalising this as an inexplicable feeling of emptiness and disorientation.” (King, 2013), perhaps she is searching for something to centre her identity, clues about her identity, lost following the erasure. The second quote referring to a happiness that neither feels as they seek their lost identities and attempt to rebuild them by regaining the erased memories, while also giving context and title to the film. It is at the flat that Clementine receives a letter from Mary with details and audio tape of her memory erasure which Clementine plays in Joel’s car stereo, which reveals all to Joel and causes another breakup.

Well I’m not sure how they both subconsciously knew to meet there, as we are only witnesses to Joel’s memory erasure, so how did Clementine know, or have reason to go to Montauk that day? Mary the clinics secretary, who we learn later has also had her memory erased because of a previous relationship with Howard, quotes Friedrich Nietzsch “Blessed are the forgetful for they got the better even of their blunder” and again this time Alexander Pope “How happy is the blameless vessels lot! The world forgot. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” The first quote appears to indicate that the erasure of their memories solves all their problems but of course it does not do that at all, in fact they both appear to have major identity issues, having lost part of themselves by having the memories of each other erased. Each looking for what they have lost, Clementine almost at the edge of madness as she searches her home for what? In the article by Gemma King “I don’t know. I’m lost. I’m scared. I feel like I’m disappearing . . . nothing makes sense to me.” It is clear that Clementine feels the rupture in the continuity of her experience caused by the erasure, verbalising this as an inexplicable feeling of emptiness and disorientation.” (King, 2013), perhaps she is searching for something to centre her identity, clues about her identity, lost following the erasure. The second quote referring to a happiness that neither feels as they seek their lost identities and attempt to rebuild them by regaining the erased memories, while also giving context and title to the film. It is at the flat that Clementine receives a letter from Mary with details and audio tape of her memory erasure which Clementine plays in Joel’s car stereo, which reveals all to Joel and causes another breakup.  However, Clementine follows Joel to his home where he is listening to his audio recording of his memory erasure, which also reveals his reasons for having his memory wiped. Clementine appears to regret her decision for erasing Joel from her memory as does Joel and the film ends but is the final sequence of them together in the snow a future memory or is this another flashback and they are still listening to Joel’s audio tape in his home?

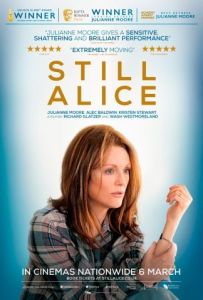

However, Clementine follows Joel to his home where he is listening to his audio recording of his memory erasure, which also reveals his reasons for having his memory wiped. Clementine appears to regret her decision for erasing Joel from her memory as does Joel and the film ends but is the final sequence of them together in the snow a future memory or is this another flashback and they are still listening to Joel’s audio tape in his home? Still Alice (2014). Alice (played by Julianne Moore) a Professor at Columbia University is having minor memory problems starting with a mind blank during a lecture, she is lost for a word. As the film progresses the memory lapses become more prevalent at one point during a run, she becomes disorientated and doesn’t appear to know where she is or which direction to go. This is a very different approach in direction to that of the Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) the conceptualisation of memory loss is more random in Still Alice and includes memory loss of words, places and people rather than the selective amnesia of Joel’s memories of Clementine. Alice having been diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s and at a relatively young age, the doctor says the disease will progress rapidly, which we see in the film’s timeline, as the memory losses appear to become more frequent. Alice worries that as the memory loss increases, she will lose more and more of her identity, which sets in motion the plan to end her life before all of her identity is gone, as in the title Still Alice, will this remain true after all the memories have been ripped away? The film draws the audience’s attention to what memories are lost, concentrating on the loss of short-term memory as Alice forgets almost immediately conversations with family members when compared with the sequences of long-term memory by using flashbacks to memories of when she was a child, with her mother, father and sister enjoying the beach. These flashbacks are triggered by a photo album with photos of herself with her mother and sister but also when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces we return via flashback to her memories of family on the beach.

Still Alice (2014). Alice (played by Julianne Moore) a Professor at Columbia University is having minor memory problems starting with a mind blank during a lecture, she is lost for a word. As the film progresses the memory lapses become more prevalent at one point during a run, she becomes disorientated and doesn’t appear to know where she is or which direction to go. This is a very different approach in direction to that of the Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) the conceptualisation of memory loss is more random in Still Alice and includes memory loss of words, places and people rather than the selective amnesia of Joel’s memories of Clementine. Alice having been diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s and at a relatively young age, the doctor says the disease will progress rapidly, which we see in the film’s timeline, as the memory losses appear to become more frequent. Alice worries that as the memory loss increases, she will lose more and more of her identity, which sets in motion the plan to end her life before all of her identity is gone, as in the title Still Alice, will this remain true after all the memories have been ripped away? The film draws the audience’s attention to what memories are lost, concentrating on the loss of short-term memory as Alice forgets almost immediately conversations with family members when compared with the sequences of long-term memory by using flashbacks to memories of when she was a child, with her mother, father and sister enjoying the beach. These flashbacks are triggered by a photo album with photos of herself with her mother and sister but also when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces we return via flashback to her memories of family on the beach.

An Everyday Magic – Cinema and Cultural Memory

An Everyday Magic – Cinema and Cultural Memory The Collective memory Reader

The Collective memory Reader Qualitative Research Methods – collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact.

Qualitative Research Methods – collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact.

This is about you, your personal skills and academic experience/abilities and why you have applied to study at this institution. This is important, basically you are selling yourself to the institution and it’s about how you can uniquely achieve your PhD research through your skillset and record of achievement thus far. For me this was my experience of documentary filmmaking and appropriate academic study in a film related subject.

This is about you, your personal skills and academic experience/abilities and why you have applied to study at this institution. This is important, basically you are selling yourself to the institution and it’s about how you can uniquely achieve your PhD research through your skillset and record of achievement thus far. For me this was my experience of documentary filmmaking and appropriate academic study in a film related subject.