Genetics

Clones and geneticS memories continued

Many other films use a similar trope, the clone that does not know it is a clone Moon (2009) Directed by Duncan Jones. Sam is a clone that is not aware that it is a clone until it meets another clone, as in the film Oblivion. This film also shares similarities with Blade Runner in regard to cloning life expectancy (3 years).

The Island (2005) Directed by Michael Bay. The big secret is that everyone working in the facility is supposedly a survivor in a Dystopian future and is in fact a clone. They are unaware that they are clones and that their sole purpose is to provide spare parts to their owners should their owners become sick or injured. While they do not have a complete memory of their true lives and identities and no memory of the very much safe and undamaged World outside, they have genetic memories in order to be able to function and additional prosthetic memories of why they should stay in the facility.

Genetic memories while still, an area of research in the scientific world appears to offer a solution for cinema to explain how newly created and bioengineered beings that is clones can function almost immediately and complete with memories of the original subject up to the moment of activation. Just like human babies they are born with the abilities to do things, memories that control autonomous functions, for example learning to walk, do they learn this, or is it programmed into the DNA and they just remember how to do it, genetic memory?

Genetic memories

Genetic memory, simply put, is complex abilities and actual sophisticated knowledge inherited along with other more typical and commonly accepted physical and behavioral characteristics. (Treffert, 2015)

In Science Fiction films the trope of genetic memory creates the possibility for a way of defining how clones are able to remember the original subjects’ memories. Genetic memories are memories that are encoded in genetics and may be passed on through the generations. Explicitly in the film examples, I have chosen, genetic memories are passed on from the original subject and embedded within the clone’s genetics, as part of its very DNA. The general belief is that while cloning has been proven, creating a clone with complete memories of the original would not be so easily achieved. As Evans writes “[f]or most cloning depicted in the film, there is no cloning of memories. Only the biology is duplicated ( . . . ) Duplicating a person’s memories and learning is many orders of magnitude more difficult to accomplish than copying the genetics ( . . . )“ (Evans, 2011)

Another many-time replicated trope is the idea of the clone who remembers their past life. Alien Resurrection (1997) Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. This film depicts a form of genetic memory remembered in a clone, Ripley 8, although in this film it is the xenomorph that is credited with the ability to retain memories across the generations. In the final scenes of Alien3 (1992) Directed by David Fincher, Ripley’s character is shown falling into a furnace clutching the xenomorph to her chest, almost certainly to her death. Alien Resurrection opens on the premise that the scientists are attempting to recreate the xenomorph Queen from Ripley’s clone created through the recovered genetic material. By surgically removing it from the body of a fully grown clone of Ripley. We see Ripley 8 (clone number 8) who exhibits a combination of human and xenomorph genetics combined with Ripleys DNA beginning to remember her past life in the canteen scene, which surprises the scientists who despite the initial desire to terminate Ripley’s clone, ending experiment because of this, but decide not to, to see what happens. While not an authoritative source of information the consensus among fans contributing to the Alien Anthology Wiki , which states that “[t]he Xenomorphs possesses the ability to pass on their memories genetically, and because of this Ripley 8 has “inherited” vague memories that belonged to the original Ellen Ripley as well as the Xenomorph”. (Ripley 8 | Alien Anthology Wiki | Fandom, no date)

Another example of the clone remembering their past life through genetic memories.

The Fifth Element (1997) Directed by Luc Besson is another excellent example of a film where genetics DNA and genetic memory are key to the progress of the narrative. When the Fifth Element is transported back to the Earth in a spaceship and is destroyed on route by the Mangalores, there is only one survivor. The only survivor turns out to be just a severed hand holding a case. The scientists use the DNA material from the hand to create a clone. Leeloo is fully grown and complete with all her memories, grown in a machine, we see the cloning method as each layer is formed, the bones, muscles, and veins with the final process, exposure to ultraviolet rays to form the skin. Leeloo is complete both in mind and body, the genetic memories encoded into her DNA. The memories are not complete, a scene shows her watching television, rapidly scrolling through images to catch up on recent Earth’s history, martial arts, and society.

A final example of this trope, the clone remembering the donor’s life’s memories can be watched in a science fiction television series Enterprise (2001 – 2005), in Series 3 episode 10 Similitude (2003). Trip is injured when the engines malfunction and the only solution offered by the ship’s doctor is to grow a clone from Trip’s DNA using an alien larva. This rapidly growing clone with Trips genetics and with a lifespan of just 15 days will have its organs harvested to heal a dying Trip. As the episode progresses the clone grows to adulthood with all of Trips memories complete. As in Alien Resurrection, it is the xenomorph that is credited with being able to recreate the memories from the donor’s DNA. (‘Enterprise’ Similitude (TV Episode 2003) – IMDb, no date)

Bibliography

Anon (2017) Ghost in the Shell (2017) – Quotes – IMDb. Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1219827/quotes?ref_=tttrv_sa_3 (Accessed: 21 January 2020).

Bordwell, D. (2006) The Way Hollywood Tells It. University of California Press.

Burgoyne, R. (2003) ‘Memory, history and digital imagery in contemporary film’, in Grainge, P. (ed.) Memory and popular film.

‘Enterprise’ Similitude (TV Episode 2003) – IMDb (no date). Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0572236/?ref_=ttep_ep10 (Accessed: 7 March 2021).

Evans, J. (2011) Top 5 Sci-Fi Movies About Cloning. Available at: https://sciencefiction.com/2011/12/08/top-5-sci-fi-movies-about-cloning/ (Accessed: 7 February 2021).

Gateward, F. (2004) Genders OnLine Journal – Presenting innovative theories in art, literature, history, music, TV and film., Genders Online Journal. Available at: https://cdn.atria.nl/ezines/IAV_606661/IAV_606661_2010_51/g40_gateward.html (Accessed: 17 February 2021).

Grainge, P. (2018) ‘Memory and popular film’, in Memory and popular film. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-4726.2004.141_16.x.

Hayward, S. (2018) Cinema Studies The Key Concepts. Fitth, Book. Fitth.

Hiatt, B. (2003) Answers to ‘“Matrix Reloaded”’ burning questions | EW.com. Available at: https://ew.com/article/2003/05/23/answers-matrix-reloaded-burning-questions/ (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Kilbourn, R. (2019) ‘RE-WRITING ” REALITY “: READING ” THE MATRIX ” Author ( s ): RUSSELL J . A . KILBOURN Source : Revue Canadienne d ’ Études cinématographiques / Canadian Journal of Film Studies , Published by : University of Toronto Press Stable URL : https://www.jstor.or’, 9(2), pp. 43–54.

Landsberg, A. (2004) Prosthetic Memory : The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=107227&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,shib&user=s1523151.

Landsberg, A. (2016) ‘Prosthetic Memory: Total Recall and Blade Runner’, Body & society. SAGE Publications, 1(3–4), pp. 175–189. doi: 10.1177/1357034×95001003010.

Lopes, M. M., Ncc, I. and Bastos, P. B. (2019) ‘Memory ( Enhancement ) and Cinema : an exploratory creative overview’.

Lury, C. (2013) Prosthetic Culture, Prosthetic Culture. doi: 10.4324/9780203425251.

Opam, K. (2017) Ghost in the Shell review: a solid film built on a broken foundation – The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/29/15114902/ghost-in-the-shell-review-scarlett-johansson (Accessed: 21 January 2020).

Radstone, S. (2010) ‘Cinema and memory’, in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates. Fordham University Press, pp. 325–342.

Radstone, S. and Hodgkin, K. (2003) Regimes of memory, Regimes of Memory. doi: 10.4324/9780203391532.

Radstone, Sussanah and Schwarz, B. (2010) ‘Memory’, in Radstone, Susannah and Shwarz, B. (eds), pp. 325–342.

replicant, n. : Oxford English Dictionary (no date). Available at: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/162877?redirectedFrom=replicant#eid (Accessed: 22 April 2020).

Rife, S. (2014) Oblivion: Trouble with Cinematic Memory – Offscreen, Offscreen. Available at: https://offscreen.com/view/oblivion-cinematic-memory (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Ripley 8 | Alien Anthology Wiki | Fandom (no date). Available at: https://alienanthology.fandom.com/wiki/Ripley_8 (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Schwab, G. (1987) ‘Cyborgs. Postmodern Phantasms of Body and Mind’, Discourse, 9, pp. 64–84. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389089.

Sloat, S. (2017) False Memories in ‘Blade Runner’ Could’ve Been Solved with Science. Available at: https://www.inverse.com/article/37496-blade-runner-2049-false-memories-ryan-gosling (Accessed: 16 March 2020).

Spies Like Us: Harry Palmer, the Everyday Hero of ‘The Ipcress File’ • Cinephilia & Beyond (no date). Available at: https://cinephiliabeyond.org/spies-like-us-harry-palmer-everyday-hero-ipcress-file/ (Accessed: 1 February 2021).

Sprengnether, M. (2012) ‘Freud as memoirist: A reading of “Screen Memories”’, American Imago, 69(2), pp. 215–239. doi: 10.1353/aim.2012.0008.

Treffert, D. (2015) Genetic Memory: How We Know Things We Never Learned – Scientific American Blog Network. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/genetic-memory-how-we-know-things-we-never-learned/ (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Warner Brothers (2017) Blade Runner 2049 (2017) – IMDb. Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1856101/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0 (Accessed: 5 May 2020).

Journal entry: These are examples of my PhD research and research progress. They may include essays, extensive notes, and even videos. A Journal entry isn’t usually a predictable addition, as I upload these after completing a small project or essay, so they are uploaded at random times and dates.

Journal entry: These are examples of my PhD research and research progress. They may include essays, extensive notes, and even videos. A Journal entry isn’t usually a predictable addition, as I upload these after completing a small project or essay, so they are uploaded at random times and dates.

Oblivion (2013) Jack is a clone, number 49, but he does not know this because his memories are not his own. His prosthetic memory is of the Earth’s triumph and the defeat of an Alien invasion. That his role now as a Drone repair technician is helping to protect a desolate Earth from the few remaining Alien survivors. But in truth the opposite is true, the Alien Invasion was victorious, and Jack is unknowingly carrying out the Alien’s Avatar directions, by assisting Sally to strip the Earth of its few remaining resources. In truth, the aliens he is fighting are actually Earth’s real survivors, Scavengers or Scav’s as they are referred to.

Oblivion (2013) Jack is a clone, number 49, but he does not know this because his memories are not his own. His prosthetic memory is of the Earth’s triumph and the defeat of an Alien invasion. That his role now as a Drone repair technician is helping to protect a desolate Earth from the few remaining Alien survivors. But in truth the opposite is true, the Alien Invasion was victorious, and Jack is unknowingly carrying out the Alien’s Avatar directions, by assisting Sally to strip the Earth of its few remaining resources. In truth, the aliens he is fighting are actually Earth’s real survivors, Scavengers or Scav’s as they are referred to. As events unfold, he begins to break through the artificial and false prosthetic memories and begin to remember the reality of what happened, eventually overriding the prosthetic memories in the process. One of the key events in understanding his true situation and identity is the chance meeting of his clone, duplicating his role in a different zone. As in the film Ghost in the Shell, the false memories begin to break down. Jack is a clone, yet he appears to retain the memories of the original Jack, hidden behind the false prosthetic memories imprinted on his brain by Sally. As Lury argues in a culture created through the use of prosthetic memory that this culture that is a [p]rosthetic culture thus provides a novel context for understandings of the person and of self-identity”. (Lury, 2013: 11). What I would argue and as Lury appears to suggest in her argument, is that Jack’s identity up to this point does not include the possibility that he is a clone, that he is uniquely Jack, not a clone and his prosthetic memories are real and inform his identity and purpose, which only changes as Jack learns his true identity.

As events unfold, he begins to break through the artificial and false prosthetic memories and begin to remember the reality of what happened, eventually overriding the prosthetic memories in the process. One of the key events in understanding his true situation and identity is the chance meeting of his clone, duplicating his role in a different zone. As in the film Ghost in the Shell, the false memories begin to break down. Jack is a clone, yet he appears to retain the memories of the original Jack, hidden behind the false prosthetic memories imprinted on his brain by Sally. As Lury argues in a culture created through the use of prosthetic memory that this culture that is a [p]rosthetic culture thus provides a novel context for understandings of the person and of self-identity”. (Lury, 2013: 11). What I would argue and as Lury appears to suggest in her argument, is that Jack’s identity up to this point does not include the possibility that he is a clone, that he is uniquely Jack, not a clone and his prosthetic memories are real and inform his identity and purpose, which only changes as Jack learns his true identity. The Maze Runner (2014) The film opens with the main protagonist transferring to the surface from a subterranean location. The main protagonist, Thomas arrives with no memory except in a few days he remembers his name. His memory has been wiped selectively, his name the only memory and identity that he knows, just like all the others. They do not know where they are in the world or the reason for their incarceration in the Glade. They are determined to escape and so each day a team (runners) explores the maze outside of the Glade, the aim to identify a route out of the false habitat The Glade and escape back to the real world.

The Maze Runner (2014) The film opens with the main protagonist transferring to the surface from a subterranean location. The main protagonist, Thomas arrives with no memory except in a few days he remembers his name. His memory has been wiped selectively, his name the only memory and identity that he knows, just like all the others. They do not know where they are in the world or the reason for their incarceration in the Glade. They are determined to escape and so each day a team (runners) explores the maze outside of the Glade, the aim to identify a route out of the false habitat The Glade and escape back to the real world. Eventually, they escape only to find themselves in a laboratory, everyone appears to be dead, and the laboratory shows damage from a battle between the scientists and an unknown armed group. It is at this point a video starts to play. In the video the scientist reveals that they have been the subjects of an experiment, the world is a ruin destroyed by Sun flares and an unknown plague called the Flare, as the video plays an armed battle is revealed in the background. As the battle reaches a climax the scientist commits suicide in front of the camera rather than be captured. But the video is a lie its intention to create false memories, prosthetic memories in the group of survivors. As the survivors are seemingly rescued from the laboratory the next scene reveals the scientist who killed herself in the video alive and explaining to the other scientists to prepare for stage 2 of the experiment. The staging set in the laboratory and false memories of past events are essential in preparing the survivors for the next stage of the experiment. The video manipulating the memories of the survivors who because of their memory wipes cannot make any comparison between what they know and what they have been told

Eventually, they escape only to find themselves in a laboratory, everyone appears to be dead, and the laboratory shows damage from a battle between the scientists and an unknown armed group. It is at this point a video starts to play. In the video the scientist reveals that they have been the subjects of an experiment, the world is a ruin destroyed by Sun flares and an unknown plague called the Flare, as the video plays an armed battle is revealed in the background. As the battle reaches a climax the scientist commits suicide in front of the camera rather than be captured. But the video is a lie its intention to create false memories, prosthetic memories in the group of survivors. As the survivors are seemingly rescued from the laboratory the next scene reveals the scientist who killed herself in the video alive and explaining to the other scientists to prepare for stage 2 of the experiment. The staging set in the laboratory and false memories of past events are essential in preparing the survivors for the next stage of the experiment. The video manipulating the memories of the survivors who because of their memory wipes cannot make any comparison between what they know and what they have been told

Prosthetic Memory in Science Fiction

Prosthetic Memory in Science Fiction

Consider Blade Runner 2049 (2017) and its prequel these two films are almost a definition for advanced technology and prosthetic memory. The film follows on from the original Blade Runner (1982) “Thirty years after the events of Blade Runner (1982), a new Blade Runner, L.A.P.D. Officer “K” (Ryan Gosling), unearths a long-buried secret that has the potential to plunge what’s left of society into chaos. K’s discovery leads him on a quest to find Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former L.A.P.D. Blade Runner, who has been missing for thirty years”. (Warner Brothers, 2017) As the producer’s state, this sequel follows on from the original Blade Runner (1982) albeit with a 30-year gap from where in the final scenes of the extended version of the film (The Directors Cut, 1992) Deckard and Rachael are together in Deckard’s flying car escaping for a new life, somewhere outside of Los Angeles. The spectator is left to make their own conclusions as to what happens to them in the future, with the narrator suggesting that Rachael might not have the limited 4-year life span of a replicant, which is one of the key premises for the film, the replicants seeking an extension to their limited 4 year life span.

Consider Blade Runner 2049 (2017) and its prequel these two films are almost a definition for advanced technology and prosthetic memory. The film follows on from the original Blade Runner (1982) “Thirty years after the events of Blade Runner (1982), a new Blade Runner, L.A.P.D. Officer “K” (Ryan Gosling), unearths a long-buried secret that has the potential to plunge what’s left of society into chaos. K’s discovery leads him on a quest to find Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former L.A.P.D. Blade Runner, who has been missing for thirty years”. (Warner Brothers, 2017) As the producer’s state, this sequel follows on from the original Blade Runner (1982) albeit with a 30-year gap from where in the final scenes of the extended version of the film (The Directors Cut, 1992) Deckard and Rachael are together in Deckard’s flying car escaping for a new life, somewhere outside of Los Angeles. The spectator is left to make their own conclusions as to what happens to them in the future, with the narrator suggesting that Rachael might not have the limited 4-year life span of a replicant, which is one of the key premises for the film, the replicants seeking an extension to their limited 4 year life span.

One of the men in the life raft appears to be recalling a memory and calls out the name Kath, the visuals of the rippling water is once again deployed to flashback to a scene of home before the war. This time the flashback visuals are accompanied by the sound of the sea overlayed onto the music as the shot cross dissolves to a shot of two people one of them the sailor discussing the likelihood of coming of the war. The scene matching the one between the Captain and his wife, two households at each end of the social classes seemingly in agreement that war is coming and that despite the difference in social class they are all in this together. As the scene plays out the ripple effect visuals and the sound of the sea prepare the spectator for a return to the chronological time line but instead it flashbacks cross fading back in time returning to the scene of the commissioning of the ship and the address by the Captain to the ship’s crew before their first voyage. This would initially confuse the spectator until part of the scene plays out and the disorientation ends? The flashback is sequence provides essential information, the preparedness of the ship and its crew as war is declared. As Turim states “[t]his logic of time and space is ultimately what helps the viewer to distinguish a flashback from a purely imaginary sequence or an arbitrary narrative disruption”. (Turim, 2013: 11)

One of the men in the life raft appears to be recalling a memory and calls out the name Kath, the visuals of the rippling water is once again deployed to flashback to a scene of home before the war. This time the flashback visuals are accompanied by the sound of the sea overlayed onto the music as the shot cross dissolves to a shot of two people one of them the sailor discussing the likelihood of coming of the war. The scene matching the one between the Captain and his wife, two households at each end of the social classes seemingly in agreement that war is coming and that despite the difference in social class they are all in this together. As the scene plays out the ripple effect visuals and the sound of the sea prepare the spectator for a return to the chronological time line but instead it flashbacks cross fading back in time returning to the scene of the commissioning of the ship and the address by the Captain to the ship’s crew before their first voyage. This would initially confuse the spectator until part of the scene plays out and the disorientation ends? The flashback is sequence provides essential information, the preparedness of the ship and its crew as war is declared. As Turim states “[t]his logic of time and space is ultimately what helps the viewer to distinguish a flashback from a purely imaginary sequence or an arbitrary narrative disruption”. (Turim, 2013: 11) As the flashback continues the scene joins each of the main protagonists as they celebrate Christmas at their respective homes, each separated by class but joined together in celebration, again promoting this feeling of they are all in this war together. As the scene comes to an end the Captains wife echo’s the words from the narration at the start of the flashback, and with the shot rippling, the music overlayed with the sound of the waves the shot crossfades back to the chronological timeline and re-joins the survivors in the life raft as they contemplate the loss of their ship as it begins to sink below the surface. The flashbacks in this film appear to be derived from the personal memories of each of the protagonists and as Turim suggests “If flashbacks give us images of memory, the personal archives of the past, they also give us images of history, the shared and recorded past.” (Turim, 2014: 2) The flashbacks occur with increasing regularity as the survivor’s each revisit memories of events of their home and relationships before the ship sailed, each a personal memory of their lives before the war. Triggered by events and linked through images and sounds, for example the tattoo on the injured sailors arm says ‘Freda’ which links back to a memory of the first meeting between the survivor and Freda on a train journey. This, his future wife, which through another flashback the spectator joins the scene of their marriage before returning back to the chronological timeline and the scene of the life raft.

As the flashback continues the scene joins each of the main protagonists as they celebrate Christmas at their respective homes, each separated by class but joined together in celebration, again promoting this feeling of they are all in this war together. As the scene comes to an end the Captains wife echo’s the words from the narration at the start of the flashback, and with the shot rippling, the music overlayed with the sound of the waves the shot crossfades back to the chronological timeline and re-joins the survivors in the life raft as they contemplate the loss of their ship as it begins to sink below the surface. The flashbacks in this film appear to be derived from the personal memories of each of the protagonists and as Turim suggests “If flashbacks give us images of memory, the personal archives of the past, they also give us images of history, the shared and recorded past.” (Turim, 2014: 2) The flashbacks occur with increasing regularity as the survivor’s each revisit memories of events of their home and relationships before the ship sailed, each a personal memory of their lives before the war. Triggered by events and linked through images and sounds, for example the tattoo on the injured sailors arm says ‘Freda’ which links back to a memory of the first meeting between the survivor and Freda on a train journey. This, his future wife, which through another flashback the spectator joins the scene of their marriage before returning back to the chronological timeline and the scene of the life raft.

In the case study of the film The Limey (1999) the narrative has multiple examples of using flashbacks. Through these flashbacks and the creative use of the editing process appears to make it seem as if the film is always looking backwards as the Director intended, the fragmented editing process represents the fragmentation of the main protagonist’s, Wilson’s memory. In an interview for Rolling Stone magazine the director Soderbergh states that “[g]iven its premise, it seemed there was some possibility to recraft it into a memory piece”. (Fear, 2019) There are flashbacks within flashbacks and flashbacks looking back to a past that Wilson could not have participated. For example, the flashback to a past with appears to be a young Wilson and Jenny, this what we would call a meta-flashback with footage sourced from another film, by the Director Ken Loach, Poor Cow (1967). This meta-flashback integrates so well into The Limey’s linear timeline so that the spectator doesn’t

In the case study of the film The Limey (1999) the narrative has multiple examples of using flashbacks. Through these flashbacks and the creative use of the editing process appears to make it seem as if the film is always looking backwards as the Director intended, the fragmented editing process represents the fragmentation of the main protagonist’s, Wilson’s memory. In an interview for Rolling Stone magazine the director Soderbergh states that “[g]iven its premise, it seemed there was some possibility to recraft it into a memory piece”. (Fear, 2019) There are flashbacks within flashbacks and flashbacks looking back to a past that Wilson could not have participated. For example, the flashback to a past with appears to be a young Wilson and Jenny, this what we would call a meta-flashback with footage sourced from another film, by the Director Ken Loach, Poor Cow (1967). This meta-flashback integrates so well into The Limey’s linear timeline so that the spectator doesn’t

In Anna (2019) the flashbacks use classical conventions for entering and exiting for example, flashes to white, fades a cross dissolve combined with the sounds of a camera’s shutter operation. A lengthy flashback with flashbacks within it, provides some of the origins of Anna’s character to inform the spectator through these flashback sequences details of her background and her training as a spy. The flashbacks inform the spectator who now has some understanding as to how in one scene a market stall seller in Russia makes the jump into a modelling job in the Paris fashion industry. Then in a later scene from fashion model to an International assassin. This fits in perfectly with a quotation by Bordwell who states “Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does.” (Bordwell, 2009). The use of intertitles at the beginning and the end of the sequence clearly indicates the start and ending of the flashback and where in the past that the events occur, although the much earlier childhood flashbacks are not so indicated, instead these use the classical conventions of fades, sound and flashes to white to enter and exit the flashback sequences. As Bordwell states “If your flashbacks skip around a lot, you might worry about viewers’ losing their bearings. So to help out, you might add superimposed titles identifying the time and place of the scene.” (Bordwell, Thompson and Smith, 2016: 75). The concept of using intertitles to indicate changes in the linear timeline, harks back to early silent cinema and classical Hollywood cinema, but as I have already discussed this has also been used in contemporary films for example Anna (2019) and Iron Man (2008).

In Anna (2019) the flashbacks use classical conventions for entering and exiting for example, flashes to white, fades a cross dissolve combined with the sounds of a camera’s shutter operation. A lengthy flashback with flashbacks within it, provides some of the origins of Anna’s character to inform the spectator through these flashback sequences details of her background and her training as a spy. The flashbacks inform the spectator who now has some understanding as to how in one scene a market stall seller in Russia makes the jump into a modelling job in the Paris fashion industry. Then in a later scene from fashion model to an International assassin. This fits in perfectly with a quotation by Bordwell who states “Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does.” (Bordwell, 2009). The use of intertitles at the beginning and the end of the sequence clearly indicates the start and ending of the flashback and where in the past that the events occur, although the much earlier childhood flashbacks are not so indicated, instead these use the classical conventions of fades, sound and flashes to white to enter and exit the flashback sequences. As Bordwell states “If your flashbacks skip around a lot, you might worry about viewers’ losing their bearings. So to help out, you might add superimposed titles identifying the time and place of the scene.” (Bordwell, Thompson and Smith, 2016: 75). The concept of using intertitles to indicate changes in the linear timeline, harks back to early silent cinema and classical Hollywood cinema, but as I have already discussed this has also been used in contemporary films for example Anna (2019) and Iron Man (2008). In another case study the film The Notebook (2004), the flashbacks are used to link to past events, the memories of a past forgotten in its entirety by the central character, Allie. Duke, Allie’s husband uses the notebook, from which the film’s title is derived, as a means of misdirection, to be not seen as drawing upon his own memories in the retelling of what is their story that is revealed in the flashbacks. Duke appears to read from his notebook in the hope that Allie will regain her memory of their past life together. In many respects this misdirection works, as Allie believes the story is of a couple unknown to her, an interesting story of young love. That is true until she has a lucid moment and she remembers that Duke is her husband and the story he has been telling her from the notebook, is their own. One of the possible reasons for this filmmaking approach and the use of the flashbacks is to also keep the spectator in suspense of the identity of the young couple in the flashbacks to create a mystery. That is until a point in the film where it becomes clear that they and the young couple from the flashbacks are one and the same. A useful analogy could be derived from Theatre as Hugo Münsterberg the psychologist argues “[u]nderstanding a theatrical performance, for example, relies on our remembering the sequence of scenes that preceded the one that is before us. A character can draw attention to an earlier scene, stage props, lighting and music can also suggest these to us, but the scene itself cannot be directly “replayed” before our eyes. With film, however, things are different. The act of remembering can be screened, so to speak, before our very eyes thanks to the use of flashbacks. (Colman, 2012: 34).

In another case study the film The Notebook (2004), the flashbacks are used to link to past events, the memories of a past forgotten in its entirety by the central character, Allie. Duke, Allie’s husband uses the notebook, from which the film’s title is derived, as a means of misdirection, to be not seen as drawing upon his own memories in the retelling of what is their story that is revealed in the flashbacks. Duke appears to read from his notebook in the hope that Allie will regain her memory of their past life together. In many respects this misdirection works, as Allie believes the story is of a couple unknown to her, an interesting story of young love. That is true until she has a lucid moment and she remembers that Duke is her husband and the story he has been telling her from the notebook, is their own. One of the possible reasons for this filmmaking approach and the use of the flashbacks is to also keep the spectator in suspense of the identity of the young couple in the flashbacks to create a mystery. That is until a point in the film where it becomes clear that they and the young couple from the flashbacks are one and the same. A useful analogy could be derived from Theatre as Hugo Münsterberg the psychologist argues “[u]nderstanding a theatrical performance, for example, relies on our remembering the sequence of scenes that preceded the one that is before us. A character can draw attention to an earlier scene, stage props, lighting and music can also suggest these to us, but the scene itself cannot be directly “replayed” before our eyes. With film, however, things are different. The act of remembering can be screened, so to speak, before our very eyes thanks to the use of flashbacks. (Colman, 2012: 34).

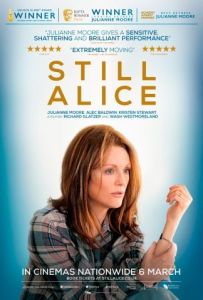

Another example of flashbacks as I have mentioned is the telling flashback, an example can be found in the film Still Alice (2014) this is also a flashback where the main protagonist is not recounting the event from memory. Alice a former professor of English is living with early onset Alzheimer’s and her memory of this event is missing. The flashback, a video message from the past, recorded by Alice herself, is a form of telling rather than a prosthetic flashback. The flashback an instructional video on how to commit suicide was created in the past while Alice still had her memories and most of her identity. The video is a message to a future Alice who she fully expected to have significant memory loss as the disease progressed, also to have no memory of recording the video. The film has a scene showing Alice procuring the drugs needed for a suicide earlier in the film and in linear time and the reason for that scene is a revealed later in the flashback. To explain why I believe this example may not constitute a prosthetic memory as although it is delivered in the form of a video from the past that Alice did experience those events depicted in the video flashback even though she has no memory of them. As Professor Alison Landsberg who specialises in mind studies states “Prosthetic memories are adopted as the result of a person’s experience with a mass cultural technology of memory that dramatizes or recreates a history he or she did not live.” (Landsberg, 2004: 4) On this basis and regarding this flashback example it could be argued that this example does not constitute a prosthetic memory. However, this does indicate an interesting area for further research into the link between video and memory, with video being considered another form of memory and on a wider consideration all visual formats could constitute a representation of memory, see chapter 2.

Another example of flashbacks as I have mentioned is the telling flashback, an example can be found in the film Still Alice (2014) this is also a flashback where the main protagonist is not recounting the event from memory. Alice a former professor of English is living with early onset Alzheimer’s and her memory of this event is missing. The flashback, a video message from the past, recorded by Alice herself, is a form of telling rather than a prosthetic flashback. The flashback an instructional video on how to commit suicide was created in the past while Alice still had her memories and most of her identity. The video is a message to a future Alice who she fully expected to have significant memory loss as the disease progressed, also to have no memory of recording the video. The film has a scene showing Alice procuring the drugs needed for a suicide earlier in the film and in linear time and the reason for that scene is a revealed later in the flashback. To explain why I believe this example may not constitute a prosthetic memory as although it is delivered in the form of a video from the past that Alice did experience those events depicted in the video flashback even though she has no memory of them. As Professor Alison Landsberg who specialises in mind studies states “Prosthetic memories are adopted as the result of a person’s experience with a mass cultural technology of memory that dramatizes or recreates a history he or she did not live.” (Landsberg, 2004: 4) On this basis and regarding this flashback example it could be argued that this example does not constitute a prosthetic memory. However, this does indicate an interesting area for further research into the link between video and memory, with video being considered another form of memory and on a wider consideration all visual formats could constitute a representation of memory, see chapter 2. In another example of memory loss this time in the film Still Alice (2014) the use of flashbacks are used to reveal how memory loss has also resulted in a loss of Alice’s identity with Alice’s memory losses focussed on the loss of short-term memory. For example, Alice forgets almost immediately conversations she has had with family members but retains long term memories shown by using flashbacks to past events and memories of when she was a child. These flashbacks are revisited time and again of her with her mother, father and sister enjoying a holiday on the beach. These flashbacks are visually triggered through the viewing of photos in a photo album of family members, those of her younger self with her mother and sister. However not all flashbacks are triggered in this way for example, when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces this action also triggers a flashback sequence and a return to her memories of family time on the beach. These series of flashbacks are significant to the narrative with the return to the memories of family time on the beach, Alice with only the long-term memories remaining her actions and visuals triggering flashbacks to this memory. As the short-term memories fade away and with this, the loss of her identity. Cinema is fascinated with memory as Susannah Radstone a Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of South Australia states “The cinema’s long-standing and intimate relationship with memory is revealed in cinema language’s adoption of terms associated with memory—the ‘‘flashback’’ and the ‘‘fade,’’ (Radstone, 2010: 3).

In another example of memory loss this time in the film Still Alice (2014) the use of flashbacks are used to reveal how memory loss has also resulted in a loss of Alice’s identity with Alice’s memory losses focussed on the loss of short-term memory. For example, Alice forgets almost immediately conversations she has had with family members but retains long term memories shown by using flashbacks to past events and memories of when she was a child. These flashbacks are revisited time and again of her with her mother, father and sister enjoying a holiday on the beach. These flashbacks are visually triggered through the viewing of photos in a photo album of family members, those of her younger self with her mother and sister. However not all flashbacks are triggered in this way for example, when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces this action also triggers a flashback sequence and a return to her memories of family time on the beach. These series of flashbacks are significant to the narrative with the return to the memories of family time on the beach, Alice with only the long-term memories remaining her actions and visuals triggering flashbacks to this memory. As the short-term memories fade away and with this, the loss of her identity. Cinema is fascinated with memory as Susannah Radstone a Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of South Australia states “The cinema’s long-standing and intimate relationship with memory is revealed in cinema language’s adoption of terms associated with memory—the ‘‘flashback’’ and the ‘‘fade,’’ (Radstone, 2010: 3).