Flashbacks

Flashbacks

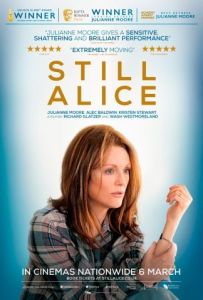

Another example of flashbacks as I have mentioned is the telling flashback, an example can be found in the film Still Alice (2014) this is also a flashback where the main protagonist is not recounting the event from memory. Alice a former professor of English is living with early onset Alzheimer’s and her memory of this event is missing. The flashback, a video message from the past, recorded by Alice herself, is a form of telling rather than a prosthetic flashback. The flashback an instructional video on how to commit suicide was created in the past while Alice still had her memories and most of her identity. The video is a message to a future Alice who she fully expected to have significant memory loss as the disease progressed, also to have no memory of recording the video. The film has a scene showing Alice procuring the drugs needed for a suicide earlier in the film and in linear time and the reason for that scene is a revealed later in the flashback. To explain why I believe this example may not constitute a prosthetic memory as although it is delivered in the form of a video from the past that Alice did experience those events depicted in the video flashback even though she has no memory of them. As Professor Alison Landsberg who specialises in mind studies states “Prosthetic memories are adopted as the result of a person’s experience with a mass cultural technology of memory that dramatizes or recreates a history he or she did not live.” (Landsberg, 2004: 4) On this basis and regarding this flashback example it could be argued that this example does not constitute a prosthetic memory. However, this does indicate an interesting area for further research into the link between video and memory, with video being considered another form of memory and on a wider consideration all visual formats could constitute a representation of memory, see chapter 2.

Another example of flashbacks as I have mentioned is the telling flashback, an example can be found in the film Still Alice (2014) this is also a flashback where the main protagonist is not recounting the event from memory. Alice a former professor of English is living with early onset Alzheimer’s and her memory of this event is missing. The flashback, a video message from the past, recorded by Alice herself, is a form of telling rather than a prosthetic flashback. The flashback an instructional video on how to commit suicide was created in the past while Alice still had her memories and most of her identity. The video is a message to a future Alice who she fully expected to have significant memory loss as the disease progressed, also to have no memory of recording the video. The film has a scene showing Alice procuring the drugs needed for a suicide earlier in the film and in linear time and the reason for that scene is a revealed later in the flashback. To explain why I believe this example may not constitute a prosthetic memory as although it is delivered in the form of a video from the past that Alice did experience those events depicted in the video flashback even though she has no memory of them. As Professor Alison Landsberg who specialises in mind studies states “Prosthetic memories are adopted as the result of a person’s experience with a mass cultural technology of memory that dramatizes or recreates a history he or she did not live.” (Landsberg, 2004: 4) On this basis and regarding this flashback example it could be argued that this example does not constitute a prosthetic memory. However, this does indicate an interesting area for further research into the link between video and memory, with video being considered another form of memory and on a wider consideration all visual formats could constitute a representation of memory, see chapter 2.

Flashbacks, memory and Identity

There is a feeling of identity loss for the main protagonists in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), each have had significant parts of their memories erased and this is explored in the film through a series of flashbacks. It is also revealed to the spectator in flashback that Mary the clinics secretary in addition to the main protagonists has also had her memory erased, because of a previous relationship with the clinics doctor. Mary quotes Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher and cultural critic, “Blessed are the forgetful for they got the better even of their blunder” (Ansell-Pearson, 1994) and again, this time quoting Alexander Pope, the British poet and translator “How happy is the blameless vessels lot! The world forgot. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” (Alexander Pope – The British Library, no date). The first quote sets the scene to indicate that the erasure of their memories solved all their problems but of course it does appear to not do that at all, in fact they both appear to have major identity issues, having lost part of themselves by having the memories of each other erased. Each of the main protagonist’s seeking for what they have lost, Clementine almost at the edge of madness as she searches her home for what? In the Bright Lights Film Journal an article presented by Gemma King, PhD Student at the Sorbonne, quotes dialogue from the film where Clementine says “I don’t know. I’m lost. I’m scared. I feel like I’m disappearing . . . nothing makes sense to me.” Clementine feels the rupture in the continuity of her experience caused by the erasure, verbalising this as an inexplicable feeling of emptiness and disorientation.” (King, 2013). Flashbacks in the film inform the spectator of their past lives and relationship, these flashbacks of which a significant number concentrate on the memories erased from the protagonist’s minds, memories that are significant in the formation of their identities. Turim states, “[f]lashback films, on the other hand, embed the process by which memory forms the individual and the social group within the narrative.” (Turim, 2014: 143).

In another example of memory loss this time in the film Still Alice (2014) the use of flashbacks are used to reveal how memory loss has also resulted in a loss of Alice’s identity with Alice’s memory losses focussed on the loss of short-term memory. For example, Alice forgets almost immediately conversations she has had with family members but retains long term memories shown by using flashbacks to past events and memories of when she was a child. These flashbacks are revisited time and again of her with her mother, father and sister enjoying a holiday on the beach. These flashbacks are visually triggered through the viewing of photos in a photo album of family members, those of her younger self with her mother and sister. However not all flashbacks are triggered in this way for example, when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces this action also triggers a flashback sequence and a return to her memories of family time on the beach. These series of flashbacks are significant to the narrative with the return to the memories of family time on the beach, Alice with only the long-term memories remaining her actions and visuals triggering flashbacks to this memory. As the short-term memories fade away and with this, the loss of her identity. Cinema is fascinated with memory as Susannah Radstone a Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of South Australia states “The cinema’s long-standing and intimate relationship with memory is revealed in cinema language’s adoption of terms associated with memory—the ‘‘flashback’’ and the ‘‘fade,’’ (Radstone, 2010: 3).

In another example of memory loss this time in the film Still Alice (2014) the use of flashbacks are used to reveal how memory loss has also resulted in a loss of Alice’s identity with Alice’s memory losses focussed on the loss of short-term memory. For example, Alice forgets almost immediately conversations she has had with family members but retains long term memories shown by using flashbacks to past events and memories of when she was a child. These flashbacks are revisited time and again of her with her mother, father and sister enjoying a holiday on the beach. These flashbacks are visually triggered through the viewing of photos in a photo album of family members, those of her younger self with her mother and sister. However not all flashbacks are triggered in this way for example, when she is struggling to remember how to tie her shoelaces this action also triggers a flashback sequence and a return to her memories of family time on the beach. These series of flashbacks are significant to the narrative with the return to the memories of family time on the beach, Alice with only the long-term memories remaining her actions and visuals triggering flashbacks to this memory. As the short-term memories fade away and with this, the loss of her identity. Cinema is fascinated with memory as Susannah Radstone a Professor of Cultural Theory at the University of South Australia states “The cinema’s long-standing and intimate relationship with memory is revealed in cinema language’s adoption of terms associated with memory—the ‘‘flashback’’ and the ‘‘fade,’’ (Radstone, 2010: 3).

- Flashbacks Draft Chapter 1

- Flashbacks Draft Chapter 1 (Part 2)

- Flashbacks Chapter One Draft continued…

Alexander Pope – The British Library (no date). Available at: https://www.bl.uk/people/alexander-pope (Accessed: 21 June 2020).

Ansell-Pearson, K. (1994) An Introduction to Nietzsche as Political Thinker, An Introduction to Nietzsche as Political Thinker. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511606144.

Bordwell, D. (1979) ‘The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.’, Film Criticism, 4(1), pp. 56–64. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44018650?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents (Accessed: 8 May 2020).

Bordwell, D. (2009) Observations on film art : Grandmaster flashback. Available at: http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2009/01/27/grandmaster-flashback/ (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Bordwell, D. (2017) Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Bordwell, D., Staiger, J. and Thompson, K. (2002) The classical Hollywood Cinema Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960.

Bordwell, D., Thompson, K. and Smith, J. (2016) Film Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business, Film Art: An Introduction.

Boucher, G. (2019) ‘The Limey’ At 20: Steven Soderbergh Revisits His “Vortex Of Terror” – Deadline. Available at: https://deadline.com/2019/12/steven-soderbergh-looks-back-the-limey-his-personal-vortex-of-terror-1202792732/ (Accessed: 10 February 2020).

Colman, F. (2012) Film, theory and philosophy: The key thinkers, Film, Theory and Philosophy: The Key Thinkers. doi: 10.5860/choice.48-0157.

Fear, D. (2019) Steven Soderbergh on the 20th Anniversary of ‘The Limey’ – Rolling Stone. Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-features/steven-soderbergh-interview-20th-anniversary-limey-921006/ (Accessed: 5 February 2020).

Geiger, J. and Rutsky, R. . (2005) Film Analysis. A Norton Reader. First. Edited by J. Geiger and R. . Rutsky. W. W. Norton & Company: Inc.

King, G. (2013) What Else Is Lost with Memory Loss? Memory and Identity in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – Bright Lights Film Journal. Available at: https://brightlightsfilm.com/what-else-is-lost-with-memory-loss-memory-and-identity-in-eternal-sunshine-of-the-spotless-mind/#.XiA2t-LANp9 (Accessed: 16 January 2020).

Landsberg, A. (2004) Prosthetic Memory : The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=107227&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,shib&user=s1523151.

Lopes, M. M., Ncc, I. and Bastos, P. B. (2019) ‘Memory ( Enhancement ) and Cinema : an exploratory creative overview’.

Musgrove, M. (2013) ‘Nestor ’ s Centauromachy and the Deceptive Voice of Poetic Memory ( Ovid Met . 12 . 182-535 ) Author ( s ): Margaret W . Musgrove Reviewed work ( s ): Published by : The University of Chicago Press Stable URL : http://www.jstor.org/stable/270542 . War and’, 93(3), pp. 223–231.

Pramaggiore, M. (2008) Film : a critical introduction. 2nd ed. Edited by T. Wallis. London: Laurence King.

Radstone, S. (2007) ‘Trauma theory: Contexts, politics, ethics’, Paragraph. Edinburgh University Press, 30(1), pp. 9–29. doi: 10.3366/prg.2007.0015.

Radstone, S. (2010) ‘Cinema and memory’, in Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates. Fordham University Press, pp. 325–342.

Rodriguez, E. (2016) Flashback | cinematography and literature | Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/flashback (Accessed: 3 June 2020).

Salt, B. (1992) Film style and technology : history and analysis. 2nd ed. London: Starword.

Turim, M. (2013) Flashbacks in film: Memory & history, Flashbacks in Film: Memory & History. Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9781315851761.

Turim, M. C. (2014) Flashbacks in film : Memory & history. Routledge.

Flashbacks

Flashbacks An example of the telling flashback can also be found in the film Oldboy (2003). In the final sequences of the film the main protagonist Dae-su is led through the sequence of events following his release from incarceration, of his being hypnotised and his actions being controlled by external events. This is delivered through an external or telling flashback the narration of these sequence of past events recounted by Woo-jin, his adversary, and revealed through a series of flashbacks. In addition, the flashbacks involving Mi-do who has also been hypnotised could not have been witnessed by the main protagonist Dae-su or Woo-jin as both was not in attendance. The flashback sequence in question is set in the past and by using a split screen with Woo-jin in one half and the flashback sequence in the other, Woo-jin through his narration describes the scenario in the flashbacks as he understands it through being informed of these events, rather than as a personal memory. However, this example of the flashback appears to conflict with another statement of Bordwell’s “If the film depicts a flashback, the jump back in time can be attributed to a character’s memory; the act of remembering thus motivates the flashback. (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 30). I suggest that Bordwell meant this statement to be preceded by “typically” as of course there are many examples of flashbacks which are not direct memories of the protagonists particularly in contemporary cinema. Such as the example from Oldboy (2003) where the flashback is not derived from a protagonist’s memory but from the retelling of events by a character not revealed to the spectator. Turim offers another more simple definition of the flashback as, “In its most general sense, a flashback is simply an image or a filmic segment that is understood as representing temporaI occurrences anterior to those in the images that preceded it”. (Turim, 2014: 14). This definition appears to fit with the example above where none of the protagonists were present in the events revealed in the flashback, and therefore a flashback not derived from the protagonist’s memory. Bordwell offers another example of a flashback which may offer an explanation “[a]n alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue” (Bordwell, 2009). Expanding upon this definition using the case study of the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

An example of the telling flashback can also be found in the film Oldboy (2003). In the final sequences of the film the main protagonist Dae-su is led through the sequence of events following his release from incarceration, of his being hypnotised and his actions being controlled by external events. This is delivered through an external or telling flashback the narration of these sequence of past events recounted by Woo-jin, his adversary, and revealed through a series of flashbacks. In addition, the flashbacks involving Mi-do who has also been hypnotised could not have been witnessed by the main protagonist Dae-su or Woo-jin as both was not in attendance. The flashback sequence in question is set in the past and by using a split screen with Woo-jin in one half and the flashback sequence in the other, Woo-jin through his narration describes the scenario in the flashbacks as he understands it through being informed of these events, rather than as a personal memory. However, this example of the flashback appears to conflict with another statement of Bordwell’s “If the film depicts a flashback, the jump back in time can be attributed to a character’s memory; the act of remembering thus motivates the flashback. (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 30). I suggest that Bordwell meant this statement to be preceded by “typically” as of course there are many examples of flashbacks which are not direct memories of the protagonists particularly in contemporary cinema. Such as the example from Oldboy (2003) where the flashback is not derived from a protagonist’s memory but from the retelling of events by a character not revealed to the spectator. Turim offers another more simple definition of the flashback as, “In its most general sense, a flashback is simply an image or a filmic segment that is understood as representing temporaI occurrences anterior to those in the images that preceded it”. (Turim, 2014: 14). This definition appears to fit with the example above where none of the protagonists were present in the events revealed in the flashback, and therefore a flashback not derived from the protagonist’s memory. Bordwell offers another example of a flashback which may offer an explanation “[a]n alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue” (Bordwell, 2009). Expanding upon this definition using the case study of the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). This can be a confusing film in many ways, particularly in the use of flashbacks, the spectator does not always receive a classical indication that the sequence is a flashback and where they are in the film’s timeline. However as Bordwell states “Flashbacks usually don’t confuse us, because we mentally rearrange the events into chronological order” (Bordwell, Thompson and Smith, 2016: 80). There is a lack of flashback conventions by this I mean the conventions associated with entering and exiting a flashback sequence are not always present. In addition, there are flashback sequences, memories of events, that as the main protagonist memory has been erased could not have been recounted by the main protagonist from memory. These flashbacks are examples of telling flashbacks where the flashback is used to inform the spectator of events that the main protagonist in this case has himself forgotten through having his memory erased. Another important use of the flashbacks is to add to the confusion of the spectator, the fragmented memory of the protagonist is represented by the out of sequence flashbacks, these sequences of events and in this example taken from the lost memories of the main protagonist. Sometimes a flashback and dream sequence can be interchangeable, Pramaggiore argues that “[i]f the plot requires a flashback or dream sequence, to minimize disruption editors will include an appropriate shot transition, such as a fade or a dissolve. Such transitions ease audiences into the new location and time. An abrupt, inexplicable shift in the time and place of an action which is not “announced” by a transition results in a cut. (Pramaggiore, 2008). Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) transitions from linear time and flashbacks without conventions just cuts and cross cuts, which can be confusing, but can also be representative of the fragmented memories of the main protagonists. As Bordwell states “Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment. (Bordwell, 2009). This opens the definition of a flashback to “a film sequence that is not present in the linear timeline”. A more recent example of the use of flashbacks can be found in the contemporary film Alita (2019) a film, much of which is concerning memory loss of the main protagonist Alita. The missing memories are explored using a series of flashbacks, revisiting long lost memories of a previous life and events, filling those character memory gaps and at the same time informing the spectator of a past life. Alita is unaware of who she is and what was and is her purpose in life. This becomes a key element in the development of the character and the films narrative as Alita embarks on a quest to recover her lost memories and therefore her identity. As Turim states “[s]ome flashbacks directly involve a quest for the answer to an enigma posed in the beginning of a narrative through a return to the past” (Turim, 2013: 24).

This can be a confusing film in many ways, particularly in the use of flashbacks, the spectator does not always receive a classical indication that the sequence is a flashback and where they are in the film’s timeline. However as Bordwell states “Flashbacks usually don’t confuse us, because we mentally rearrange the events into chronological order” (Bordwell, Thompson and Smith, 2016: 80). There is a lack of flashback conventions by this I mean the conventions associated with entering and exiting a flashback sequence are not always present. In addition, there are flashback sequences, memories of events, that as the main protagonist memory has been erased could not have been recounted by the main protagonist from memory. These flashbacks are examples of telling flashbacks where the flashback is used to inform the spectator of events that the main protagonist in this case has himself forgotten through having his memory erased. Another important use of the flashbacks is to add to the confusion of the spectator, the fragmented memory of the protagonist is represented by the out of sequence flashbacks, these sequences of events and in this example taken from the lost memories of the main protagonist. Sometimes a flashback and dream sequence can be interchangeable, Pramaggiore argues that “[i]f the plot requires a flashback or dream sequence, to minimize disruption editors will include an appropriate shot transition, such as a fade or a dissolve. Such transitions ease audiences into the new location and time. An abrupt, inexplicable shift in the time and place of an action which is not “announced” by a transition results in a cut. (Pramaggiore, 2008). Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) transitions from linear time and flashbacks without conventions just cuts and cross cuts, which can be confusing, but can also be representative of the fragmented memories of the main protagonists. As Bordwell states “Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment. (Bordwell, 2009). This opens the definition of a flashback to “a film sequence that is not present in the linear timeline”. A more recent example of the use of flashbacks can be found in the contemporary film Alita (2019) a film, much of which is concerning memory loss of the main protagonist Alita. The missing memories are explored using a series of flashbacks, revisiting long lost memories of a previous life and events, filling those character memory gaps and at the same time informing the spectator of a past life. Alita is unaware of who she is and what was and is her purpose in life. This becomes a key element in the development of the character and the films narrative as Alita embarks on a quest to recover her lost memories and therefore her identity. As Turim states “[s]ome flashbacks directly involve a quest for the answer to an enigma posed in the beginning of a narrative through a return to the past” (Turim, 2013: 24). In Alita {2019} the flashback sequence is always preceded by an act of violence where her life is in imminent danger, in these life or death struggles the flashback is triggered, in each flashback a forgotten memory is remembered. The use of violence as a trigger for the flashback and a return to a traumatic memory from the past. These flashbacks form a violent/traumatic interruption in the chronology and linear continuity of a film. The flashback in cinematic terms, is achieved by the camera zooming into one of Alita’s eyes passing through into what becomes a portal to a forgotten memory and previous life as the image flashes to white, the flash then cross dissolving into the start of the flashback sequence. This is a classical form and use of the flashback sequence, using the conventions of both visual and sound cues to enter and exit the flashback sequence. Pramaggiore a film theorist argues that “The most common example of [re-ordered chronology in a film’s plot] is the flashback, when events taking place in the present are ‘interrupted’ by images or scenes that have taken place in the past.” (Pramaggiore, 2008: 244).

In Alita {2019} the flashback sequence is always preceded by an act of violence where her life is in imminent danger, in these life or death struggles the flashback is triggered, in each flashback a forgotten memory is remembered. The use of violence as a trigger for the flashback and a return to a traumatic memory from the past. These flashbacks form a violent/traumatic interruption in the chronology and linear continuity of a film. The flashback in cinematic terms, is achieved by the camera zooming into one of Alita’s eyes passing through into what becomes a portal to a forgotten memory and previous life as the image flashes to white, the flash then cross dissolving into the start of the flashback sequence. This is a classical form and use of the flashback sequence, using the conventions of both visual and sound cues to enter and exit the flashback sequence. Pramaggiore a film theorist argues that “The most common example of [re-ordered chronology in a film’s plot] is the flashback, when events taking place in the present are ‘interrupted’ by images or scenes that have taken place in the past.” (Pramaggiore, 2008: 244).

In classical Hollywood Cinema, Casablanca has a single extended use of the flashback, the purpose is to provide background character information, in revealing to the spectator the previous relationship of the main protagonists, Rick and Ilsa. When considering the decision to use only a single extended flashback sequence in Casablanca (1942) when compared with the multiple use of flashbacks in Kitty Foyle (1940), which are just a few years apart. I am reminded of the Bordwell quote that flashbacks do not tend to confuse the spectator as we mentally put them in order, but this may not be true of the spectator in 1940s cinema. The spectators of the time may possibly have found flashbacks a new and confusing concept and this may have influenced the decision-making processes for the creators of Casablanca (1942) to limit the use to just one flashback a self-contained film within a film. As Turim quotes from the Film Encyclopaedia (New York: Perigee, 1982), “Although generally a useful device in advancing a complicated plot, the multiple flashback can be absurdly confusing.” (Turim, 2014: 247). The extended flashback sequence is set in Paris, the flashback is used to both reveal and develop the main protagonists previous relationship and simultaneously resolve some of the gaps in the film’s narrative, the unanswered questions in the opening scenes of the film for example, where does Ilsa know Rick from and what was their previous relationship, just friends or more?. Dana Polan the film theorist states that to many cinephiles Casablanca (1942) is an example of Hollywood filmmaking at its best and as Polan, a professor of cinema studies states in his Casablanca essay, “One of the great films of cult veneration, Casablanca (1942) is the perfect example of Hollywood perfection.” (Geiger and Rutsky, 2005: 363). Flashbacks in classic Hollywood cinema typically make use of a series of conventions to initiate the flashback, for example Casablanca’s flashback sequence includes several of these. Bordwell states that “[f]lashbacks can be initiated by any number and indeed types of cues. For instance, there are several cues for a flashback in a classical Hollywood film: pensive character attitude, close-up of face, slow dissolve, voice-over narration, sonic ‘flashback,’ music. In any given case, several of these will be used together” (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 5) . The flashback sequence in Casablanca uses several of what have become the classical, that is established and recognisable conventions for a flashback. For example the flashback sequence is preceded by Rick’s pensive attitude, Rick is centred in the frame with his face in close-up showing his anguish. The shot then begins to become misty/blurring with a slow dissolve into what becomes the flashback sequence. At the end of the flashback sequence similar conventions are used but using the steam emissions from the locomotive to blur the image and initiate another slow dissolve back to the current chronological order that is linear timeline. However, Casablanca is preceded by both literary and film examples of the flashback technique. The Encyclopaedia Britannica states that “The flashback technique is as old as Western literature. In the Odyssey, most of the adventures that befell Odysseus on his journey home from Troy are told in flashback by Odysseus when he is at the court of the Phaeacians”. (Rodriguez, 2016). The early use of the flashback in literature, the narrator telling the story, Musgrove, professor of humanities states …” at the beginning of his “Iliad,” Ovid uses conventions of traditional epic, especially the extended flashback, to call into question the reliability of epic narration and epic narrators and to suggest alternative perspectives on the canonical story of the Trojan War. “ (Musgrove, 2013: 2). As I stated previously flashbacks have increased in prevalence in films from the 1930s’ to varying degrees of commonplace in films over the decades. Turim states that “After cinema makes the flashback a common and distinctive narrative trait, audiences and critics were more likely to recognize flashbacks as crucial elements of narrative structure in other narrative forms.” (Turim, 2014: 20). From this example you could infer that the use of flashback conventions is well established and used to prepare the spectator for the start of the flashback and similarly out of the flashback sequence, returning to the chronological order and linear timeline.

In classical Hollywood Cinema, Casablanca has a single extended use of the flashback, the purpose is to provide background character information, in revealing to the spectator the previous relationship of the main protagonists, Rick and Ilsa. When considering the decision to use only a single extended flashback sequence in Casablanca (1942) when compared with the multiple use of flashbacks in Kitty Foyle (1940), which are just a few years apart. I am reminded of the Bordwell quote that flashbacks do not tend to confuse the spectator as we mentally put them in order, but this may not be true of the spectator in 1940s cinema. The spectators of the time may possibly have found flashbacks a new and confusing concept and this may have influenced the decision-making processes for the creators of Casablanca (1942) to limit the use to just one flashback a self-contained film within a film. As Turim quotes from the Film Encyclopaedia (New York: Perigee, 1982), “Although generally a useful device in advancing a complicated plot, the multiple flashback can be absurdly confusing.” (Turim, 2014: 247). The extended flashback sequence is set in Paris, the flashback is used to both reveal and develop the main protagonists previous relationship and simultaneously resolve some of the gaps in the film’s narrative, the unanswered questions in the opening scenes of the film for example, where does Ilsa know Rick from and what was their previous relationship, just friends or more?. Dana Polan the film theorist states that to many cinephiles Casablanca (1942) is an example of Hollywood filmmaking at its best and as Polan, a professor of cinema studies states in his Casablanca essay, “One of the great films of cult veneration, Casablanca (1942) is the perfect example of Hollywood perfection.” (Geiger and Rutsky, 2005: 363). Flashbacks in classic Hollywood cinema typically make use of a series of conventions to initiate the flashback, for example Casablanca’s flashback sequence includes several of these. Bordwell states that “[f]lashbacks can be initiated by any number and indeed types of cues. For instance, there are several cues for a flashback in a classical Hollywood film: pensive character attitude, close-up of face, slow dissolve, voice-over narration, sonic ‘flashback,’ music. In any given case, several of these will be used together” (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 5) . The flashback sequence in Casablanca uses several of what have become the classical, that is established and recognisable conventions for a flashback. For example the flashback sequence is preceded by Rick’s pensive attitude, Rick is centred in the frame with his face in close-up showing his anguish. The shot then begins to become misty/blurring with a slow dissolve into what becomes the flashback sequence. At the end of the flashback sequence similar conventions are used but using the steam emissions from the locomotive to blur the image and initiate another slow dissolve back to the current chronological order that is linear timeline. However, Casablanca is preceded by both literary and film examples of the flashback technique. The Encyclopaedia Britannica states that “The flashback technique is as old as Western literature. In the Odyssey, most of the adventures that befell Odysseus on his journey home from Troy are told in flashback by Odysseus when he is at the court of the Phaeacians”. (Rodriguez, 2016). The early use of the flashback in literature, the narrator telling the story, Musgrove, professor of humanities states …” at the beginning of his “Iliad,” Ovid uses conventions of traditional epic, especially the extended flashback, to call into question the reliability of epic narration and epic narrators and to suggest alternative perspectives on the canonical story of the Trojan War. “ (Musgrove, 2013: 2). As I stated previously flashbacks have increased in prevalence in films from the 1930s’ to varying degrees of commonplace in films over the decades. Turim states that “After cinema makes the flashback a common and distinctive narrative trait, audiences and critics were more likely to recognize flashbacks as crucial elements of narrative structure in other narrative forms.” (Turim, 2014: 20). From this example you could infer that the use of flashback conventions is well established and used to prepare the spectator for the start of the flashback and similarly out of the flashback sequence, returning to the chronological order and linear timeline.

This statement by Bordwell is also clearly represented in the opening sequence of the film Oldboy (2003) an example most importantly of a film proliferated with flashback sequences and the use several examples of the flashback conventions and elements of cinematography, involving stylised shots and flashbacks triggered by sounds. As previously mentioned, one of the key reasons for choosing Oldboy (2003) a non-Hollywood film, is for an example of the use of a variety of flashbacks and for its use of cinematography. The flashback sequences use a variety zooms, tracking shots and matching shots to enter and exit flashbacks. The opening sequence is set in the future in the form of a flashforward, a significant moment in the film as the main protagonist has just been released from 15 years of incarceration. However, the spectator is not aware that they are viewing events set in the future, this is only revealed later in the film. Bordwell argues the use of the flashforward and states that “[t]he flashforward is unthinkable in the classical narrative cinema, which seeks to retard the ending and efface the mode of narration. But in the art cinema, the flashforward functions perfectly to stress authorial presence: we must notice how the narrator teases us with knowledge that no character can have (Bordwell, 1979: 2). The meaning behind this incarceration and minutia of the imprisonment are central to the films narrative and is revealed in parts through the film’s progression in a series of memory and narrated flashbacks. One of the flashback functions is to inform the spectator of past events, but these flashbacks may not uniquely come from the memory of the protagonist, as Bordwell states “[h]aving a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t witness. (Bordwell, 2009). By subjective flashback, Bordwell almost certainly means the flashback is derived from the characters personal memory of events which is revealed in the flashback as opposed to the external telling flashback which is usually a narrated or telling flashback and therefore not taken directly from a character’s memory. For example, Oldboy (2003) the main protagonist appears in some flashbacks as his adult self, participating in the flashback and pursuing his younger self through the memory of these historical events represented in the flashback.

This statement by Bordwell is also clearly represented in the opening sequence of the film Oldboy (2003) an example most importantly of a film proliferated with flashback sequences and the use several examples of the flashback conventions and elements of cinematography, involving stylised shots and flashbacks triggered by sounds. As previously mentioned, one of the key reasons for choosing Oldboy (2003) a non-Hollywood film, is for an example of the use of a variety of flashbacks and for its use of cinematography. The flashback sequences use a variety zooms, tracking shots and matching shots to enter and exit flashbacks. The opening sequence is set in the future in the form of a flashforward, a significant moment in the film as the main protagonist has just been released from 15 years of incarceration. However, the spectator is not aware that they are viewing events set in the future, this is only revealed later in the film. Bordwell argues the use of the flashforward and states that “[t]he flashforward is unthinkable in the classical narrative cinema, which seeks to retard the ending and efface the mode of narration. But in the art cinema, the flashforward functions perfectly to stress authorial presence: we must notice how the narrator teases us with knowledge that no character can have (Bordwell, 1979: 2). The meaning behind this incarceration and minutia of the imprisonment are central to the films narrative and is revealed in parts through the film’s progression in a series of memory and narrated flashbacks. One of the flashback functions is to inform the spectator of past events, but these flashbacks may not uniquely come from the memory of the protagonist, as Bordwell states “[h]aving a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t witness. (Bordwell, 2009). By subjective flashback, Bordwell almost certainly means the flashback is derived from the characters personal memory of events which is revealed in the flashback as opposed to the external telling flashback which is usually a narrated or telling flashback and therefore not taken directly from a character’s memory. For example, Oldboy (2003) the main protagonist appears in some flashbacks as his adult self, participating in the flashback and pursuing his younger self through the memory of these historical events represented in the flashback.

The Limey (1999), The film’s Director, Soderbergh is reported to have stated “[w]e created or tried to create, meaning and emotion through repetition and juxtaposition, which again, is something that’s unique to movies. The ability to mould something and then change the meaning or alter the meaning just by reordering and repeating things, that’s unique in film.” (Boucher, 2019). The Flashback, a definition of the flashback by Maureen Turim the film theorist defines flashback as “[t]he flashback is a privileged moment in unfolding that juxtaposes different moments of temporal reference. A juncture is wrought between present and past and two concepts are implied in this juncture: memory and history.” A privileged moment that Turim refers to is where the filmmaker shares with the spectator a revelation and typically important character information in the flashback, as in photography the photograph is a shared experience between the viewer and the photographer, a privileged moment. Turim then goes on to state “Studying the flashback is not only a way of studying the development of filmic form, it is a way of seeing how filmic forms engage concepts and represent ideas. (Turim, 2013: 1-20). While Bordwell, a film theorist defines the flashback simply as “Flashback …”any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past” (Bordwell, 2009) and then goes on to define the historical use of the flashback “Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.” (Bordwell, 2009). To put the use of the flashback into greater historical context, Bordwell states that “Flashbacks are rarer in the classical Hollywood film than we normally think. Throughout the period 1917 – 60, screenwriters’ manuals usually recommended not using them; as one manual put it, ‘Protracted or frequent flashbacks tend to slow the dramatic progression”. (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 42).

The Limey (1999), The film’s Director, Soderbergh is reported to have stated “[w]e created or tried to create, meaning and emotion through repetition and juxtaposition, which again, is something that’s unique to movies. The ability to mould something and then change the meaning or alter the meaning just by reordering and repeating things, that’s unique in film.” (Boucher, 2019). The Flashback, a definition of the flashback by Maureen Turim the film theorist defines flashback as “[t]he flashback is a privileged moment in unfolding that juxtaposes different moments of temporal reference. A juncture is wrought between present and past and two concepts are implied in this juncture: memory and history.” A privileged moment that Turim refers to is where the filmmaker shares with the spectator a revelation and typically important character information in the flashback, as in photography the photograph is a shared experience between the viewer and the photographer, a privileged moment. Turim then goes on to state “Studying the flashback is not only a way of studying the development of filmic form, it is a way of seeing how filmic forms engage concepts and represent ideas. (Turim, 2013: 1-20). While Bordwell, a film theorist defines the flashback simply as “Flashback …”any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past” (Bordwell, 2009) and then goes on to define the historical use of the flashback “Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.” (Bordwell, 2009). To put the use of the flashback into greater historical context, Bordwell states that “Flashbacks are rarer in the classical Hollywood film than we normally think. Throughout the period 1917 – 60, screenwriters’ manuals usually recommended not using them; as one manual put it, ‘Protracted or frequent flashbacks tend to slow the dramatic progression”. (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson, 2002: 42).  Flashbacks were used sparingly in classical cinema when compared with its current use in contemporary cinema and the ready acceptance by the spectator and filmmaker of the flashback as a tool in the filmmakers toolkit, as I previously quoted, until the 1960s screenwriters were dissuaded from using flashbacks. Barry Salt, film historian, argues that there are two types of flashback “[t]here are two principal classes of flashbacks: those that show scenes in the past that someone is remembering in their own mind, and those that show past scenes that are being narrated by someone to an audience within the framing scene.”(Salt, 1992: 109) he also states that “[t]he earliest known example of a narrated flashback occurs in the Italian Cines film company’s (Società Italiana Cines) film La fiabe della nonne, made in the middle of 1908”. (Salt, 1992: 109). Later examples of films that use flashbacks date from 1910, states Bordwell, quoting from Turim’s research into flashbacks, Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). Bordwell goes on to state that Turim’s research indicates that “[f]lashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s”. (Bordwell, 2009). Early examples of classical Hollywood films utilising flashbacks include; Behind the Door (1919),

Flashbacks were used sparingly in classical cinema when compared with its current use in contemporary cinema and the ready acceptance by the spectator and filmmaker of the flashback as a tool in the filmmakers toolkit, as I previously quoted, until the 1960s screenwriters were dissuaded from using flashbacks. Barry Salt, film historian, argues that there are two types of flashback “[t]here are two principal classes of flashbacks: those that show scenes in the past that someone is remembering in their own mind, and those that show past scenes that are being narrated by someone to an audience within the framing scene.”(Salt, 1992: 109) he also states that “[t]he earliest known example of a narrated flashback occurs in the Italian Cines film company’s (Società Italiana Cines) film La fiabe della nonne, made in the middle of 1908”. (Salt, 1992: 109). Later examples of films that use flashbacks date from 1910, states Bordwell, quoting from Turim’s research into flashbacks, Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). Bordwell goes on to state that Turim’s research indicates that “[f]lashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s”. (Bordwell, 2009). Early examples of classical Hollywood films utilising flashbacks include; Behind the Door (1919),  An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923), His Master’s Voice (1925)’ Silence (1926), Forever After (1926), The Woman on Trial (1927), The Last Command (1928), Last Moment (1928), Mammy (1930), Such is Life (1931), The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931), Two Seconds (1932). While not an exhaustive list the prevalence of the flashbacks in the early films of the 20th century was relatively uncommon, however flashbacks in films become more common from 1930. The use of flashbacks became more widespread and popular as Turim argues “[a]fter cinema makes the flashback a common and distinctive narrative trait, audiences and critics were more likely to recognize flashbacks as crucial elements of narrative structure in other narrative forms. (Turim, 2014: 20). While Bordwell appears to agree and states “that there is a veritable cascade of titles using the flashback in the 1930s, with conventions already widely in circulation”. (Bordwell, 2009). As the use of the flashback gained greater acceptance, the flashbacks become more common and begin to make appearances across all genres in classical Hollywood films, including such iconic films as Casablanca (1942).

An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923), His Master’s Voice (1925)’ Silence (1926), Forever After (1926), The Woman on Trial (1927), The Last Command (1928), Last Moment (1928), Mammy (1930), Such is Life (1931), The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931), Two Seconds (1932). While not an exhaustive list the prevalence of the flashbacks in the early films of the 20th century was relatively uncommon, however flashbacks in films become more common from 1930. The use of flashbacks became more widespread and popular as Turim argues “[a]fter cinema makes the flashback a common and distinctive narrative trait, audiences and critics were more likely to recognize flashbacks as crucial elements of narrative structure in other narrative forms. (Turim, 2014: 20). While Bordwell appears to agree and states “that there is a veritable cascade of titles using the flashback in the 1930s, with conventions already widely in circulation”. (Bordwell, 2009). As the use of the flashback gained greater acceptance, the flashbacks become more common and begin to make appearances across all genres in classical Hollywood films, including such iconic films as Casablanca (1942).  As Bordwell states “[d]uring the 1940s, however, flashback plotting was more than a fashion. Its proliferation in all genres encouraged filmmakers to probe a range of creative possibilities. A flashback, it became evident, could yield a complex experience for the viewer”. (Bordwell, 2017: 72).

As Bordwell states “[d]uring the 1940s, however, flashback plotting was more than a fashion. Its proliferation in all genres encouraged filmmakers to probe a range of creative possibilities. A flashback, it became evident, could yield a complex experience for the viewer”. (Bordwell, 2017: 72).

John Wick (2014) Flashforward. The opening scene of John Wick crashing his SUV into a loading dock, he’s injured, his hands are bloody, he crawls to the edge of the loading dock and pulls his phone from his jacket pocket and starts to watch a video of his wife on the beach. He appears to be dying, the shot then fade to black, the main title sequence overlays the scene, JOHN WICK with the sound of an alarm clock. The film is now being revealed in flashback.

John Wick (2014) Flashforward. The opening scene of John Wick crashing his SUV into a loading dock, he’s injured, his hands are bloody, he crawls to the edge of the loading dock and pulls his phone from his jacket pocket and starts to watch a video of his wife on the beach. He appears to be dying, the shot then fade to black, the main title sequence overlays the scene, JOHN WICK with the sound of an alarm clock. The film is now being revealed in flashback.

The flatmates come into the kitchen loaded down with bags full of food which they are excited about as they unpack the bags onto the table. “there’s no toilet roll, did no one order any”? But there is Spam says Spam Guy.

The flatmates come into the kitchen loaded down with bags full of food which they are excited about as they unpack the bags onto the table. “there’s no toilet roll, did no one order any”? But there is Spam says Spam Guy.

The table is piled high with toilet roll the camera lifts up to reveal David is tied and gagged (with toilet roll). Sophie and Ja sit at the table opposite each other, as Sophie hands a toilet roll to Ja “one for you” and takes one for herself “and one for me”. David makes a growling sound and Ja leans over and stuffs more toilet roll into David’s mouth, “shut up you” says Ja.

The table is piled high with toilet roll the camera lifts up to reveal David is tied and gagged (with toilet roll). Sophie and Ja sit at the table opposite each other, as Sophie hands a toilet roll to Ja “one for you” and takes one for herself “and one for me”. David makes a growling sound and Ja leans over and stuffs more toilet roll into David’s mouth, “shut up you” says Ja. Flashback Filming and script decisions.

Flashback Filming and script decisions.